EXHIBITION AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S SHOWS THE BEAUTIFUL LOOK OF THE NIGERIAN BOURGEOISIE OF THE MID-1950S

In September 2014, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art launched an exhibition of the work of Nigerian photographer Solomon Osagie Alonge.

Alonge (1911-1994) was the official photographer at the Royal Court of Benin, but he did not document only gatherings and rituals. He also ran a studio (opened in 1942) where he took pictures of up-and-coming Nigerians of the pre-and post-independence decades.

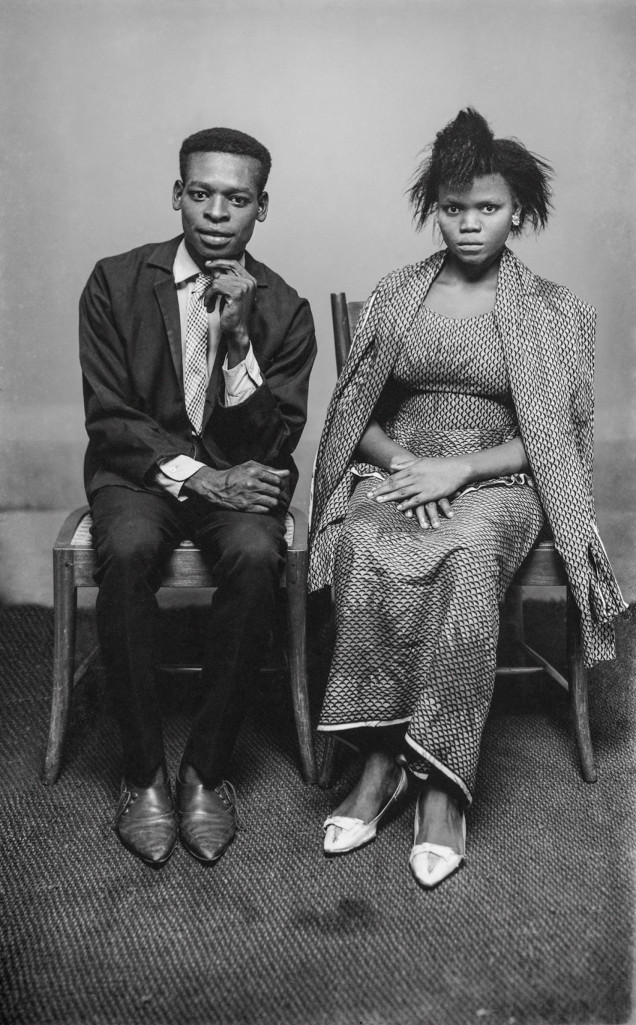

Alonge’s portraits capture history in the making, particularly the consolidation of an affluent middle-class which was eager to parade its cosmopolitanism. In these portraits, composure, hair-dressing, and sartorial sophistication are essential to the self-representation efforts of an incipient self-governing nation.

Alonge is one of many visual artists of the Fifties and Sixties which busily captured the enthusiasm and optimism of newly independent societies. Like him, Seydou Keïta in Mali, Ojeikere in Nigeria, and Oumar Ly and Mama Casset in Senegal perfected the art of studio portraiture, photographing single individuals, couples, and small groups in the traditional visual style of the first half of the 20th century that emphasized formality, restrained facial expressions, and squared-limbed poses.

Acclaimed writer Teju Cole has recently published an interesting article in the New York Times on the zeitgeist that fueled the work of Alonge and his colleagues. In particular, he highlights the photographer’s ability to capture his/her subject’s pride in showing agency and affecting self-possession. Style is the common tool the photographer and the photographed individual use to put a distance between the present and the past. “Something changed when Africans began to take photographs of one another: You can see it in the way they look at the camera, in the poses, the attitude. The difference between the images taken by colonialists or white adventurers and those made for the sitter’s personal use is especially striking in photographs of women. In the former, women are being looked at against their will, captive to a controlling gaze. In the latter, they look at themselves as in a mirror, an activity that always involves seriousness, levity and an element of wonder.”

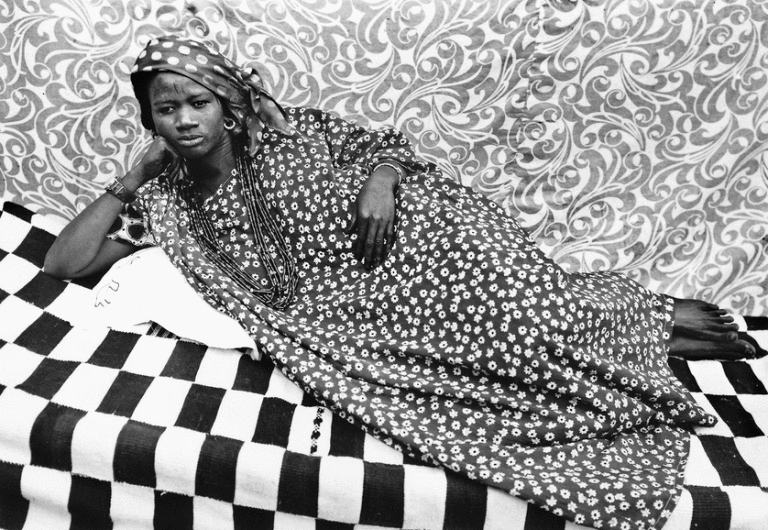

The confidence that emanates from the portraits is definitely also an effect of the studied poses and affected style of the women and men represented in them. Cole observes how the the quality and texture of the clothes directs our gaze. “A woman reclines in a long dress with fine floral patterning on a bed with a checked bedspread. Her head scarf is polka-dotted. The bed is placed in front of a wall, which is draped with a paisley cloth. And even her face is marked with cicatrices. Then we notice, emerging from this swirling field — a profusion of pattern that brings to mind Matisse at his most inventive — her delicate hands and feet, dark but subtly shaded; the right arm on which she rests her head; her narrowed eyes. Her look is self-possessed rather than seductive. She’s looking ahead but not at the camera. It is the look of someone who is thinking about herself, simultaneously outward and inward. The image challenges and delights the viewer with its complicated two-dimensional game.”

Confronted with an unnamed woman, we learn about her just by looking at what she wore and how she wore it.