STREETSTYLING OUTSIDE OF AFRICA

Brent Luvaas, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Drexel University, is an expert of streetstyling and streetwear culture. His volume Street Style: An Ethnography of Fashion Blogging is forthcoming for Bloomsbury.

As I wait to read this book, I go back to Luvaas’ other insightful writings on street culture, looking for cues to help me better flesh out my own research on African streetstylers – the Afrosartorialists.

I want to focus on two essays in particular: “Third World no More: Rebranding Indonesian Streetwear”(2013a) and “Indonesian Fashion Blogs: On the Promotional Subject of Personal Style”(2013b). Here Luvaas writes about some prominent Indonesian streetwear fashion blogs (hot chocolate and mint, Sunflares Plethora and Versicle) and grassroots labels (Unkl347, Airplane Systm, Monstore) and discusses their ambiguous position toward neoliberalism, which they seem to reject and embrace at the same time. He holds that they act as “promotional subjects [whose] personal expression and brand identification are one and the same thing” (2013b:65). Although in my case studies brand loyalty has a less prominent place, I agree that in some case studies from African countries as in Indonesia, fashion bloggers use creative self-styling to “assert their own value as creative and proactive contributors to international trends” (2013a:208, my italics).

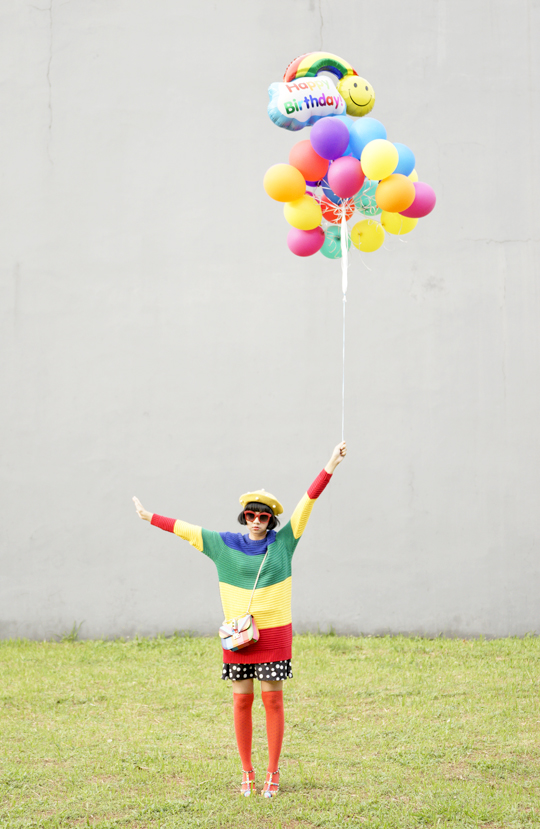

This argument in fact applies to every fashion destination where streetstyling expresses a vision of modernity that addresses, and extracts value from, the self-conscious articulation of marginality and invisibility. These are the geographical locations emerging on the “virtual territorial boundar[ies]” (2013b:59) of the international fashion scene that, in spite of their “hundreds of English-language contributions to the fashion universe […] have received little of the attention granted to bloggers from the USA and Europe. They remain largely shut out of the conversation” (2013b:58). As far as taxonomy (and my research) goes, the blogs studied by Luvaas fall under the “Narcisus” label proposed by Ida Engholm and Erik Hansen-Hansen: “a conversationally based online dialogue, driven by the blogger’s personal fashion interests and style universe” (2014:147), which “seeks to establish an open and reflective circulation between the fashion blogger, who shows herself and her style, and the reader, who is following the blogger” (Ibid.:146).

Not unlike most countries in Africa with a thriving fashion scene (national and grassroots), Indonesia continues to be regarded only as a source of manufacture. It suffers from “the mark of the Third World sweatshop”: a “post-millennial brand of global fashion marginality” (2013a: 205) that prevents rookie designers and high-end fashion labels alike to reach international consumers. And yet, with its expanding consumer base and thanks to the global outreach of social media, Indonesia is transforming the global fashion market and, in the process, its own self-representation of style hub with a strong grassroots component.

How does it do it? By networking local creativity, using the web to promote looks, garments, and other forms of DIY cultural production.

Only when Indonesians are noted immaterial producers, in addition to outsourced material manufacturers … will Indonesia be taken serious as a center of the fashion industry. Fashion, then, is a vehicle not only for personal advancement, but also for advancing the Indonesian economy and enhancing the island nation’s standing on the world stage (2013b: 61, italics in the text).

Even more important than producing unique fashion (assuming uniqueness still has value on the market), then, is this embracing of identity and localism as cultural currencies. Luvaas shows how the styles of fashion bloggers and trendsetters (themselves often the owners of big fashion brands) translate ongoing reflections about Indonesian-ness for international consumption, creating not an image of otherness, but an exotic familiarity sustained by entrepreneurship.

Stylishness is a means of individual self-assertion, but also a prerequisite to participate in the country’s advancement. It channels “influence and prestige” (2013b:60), spending power, “cosmopolitanism”, but also “Indonesian womanhood” (2013b:62). In all such instances, the self-styled body becomes the body of a nation in becoming, and, to a larger extent, of an increasingly stratified and diversified global imaginary of fashion.

Luvaas then regards streetstyling as a form of subjectivation that claims global citizenship for itself. Through representational means the consumerist subjectivity is “depicted, represented, engaged. […] The subject of Indonesia fashion blogs is […] a subject whose desire is to depict its own desires” (2013b:64). It is a representational practice with an ethos. Indeed, here as elsewhere, streetstyling entails the active participation of the youths in fashioning an ethical culture of the street out of an excess of foreign influences. “For the [bloggers] to promote is DIY. It is to take commercialization into one’s own hands, to make capitalism work for them” (2013b:70). The representational nature of the blogs analysed by Luvaas is imbued with the “DIY ethos of punk rock, a commitment to producing and distributing culture ‘on one’s own terms’, without undue influence from corporations, state interests, or the corrupting effects of capital more generally [It] activate[s] an ethic of active participation and peer cooperation, cultural democratization carried out at the ground level” (2013b:68).

Indeed, and here again I see continuities with my Afrosartorialists, self-styling empowers in ways that affect local and global politics. Luvaas holds that sartorialism is essential to the birth of urban subcultures as well as to the overall, state-sponsored refashioning of Indonesian-ness of the past decade. The former argument actually holds that, through self-styling, Indonesian youths “eschew any self-representation that smacks of … contrived national identity” (2013a:218).

Essentially, the kind of citizenship of style practiced by the bloggers is not a form of antagonism, but of proactive and precarious performances of self. Luvaas is careful Essentially, the kind of citizenship of style practiced by the bloggers is not a form of antagonism, but of proactive and precarious performances of self. Luvaas is careful to underline that the DIY ideology “was never outside the system of consumer capitalism; it was, rather, made possible by it, and it made use of capital’s incursions into Indonesia to diversify and disseminate” (2013b:70). The main aspect of this grassroots promotional strategy is to “align oneself” with “under-the-radar brands of the indie fashion circuit” and thus “secure one’s place within history” (ivi). Self-fashioning is thus an exercise in global citizenship practiced within what the youth regards as a global, democratic arena of creativity which is not, however, without its trappings.

As a final remark it is worth stressing the different promotional strategies of the youth and state-sponsored fashion actors reported by Luvaas. While the latter promotes a form of “self-orientalism” that “instill[es] Indonesian fashion with a distinct – and immediately recognizable – local flavor” (2013a:208), the former appropriates the aesthetics of global brands as “a method of symbolic participation [that] advertises [the brands’] position as part of a larger international, and often irreverent, streetwear movement” (Ibid.:219).

These co-existing positions evidence a phenomenon I see happening in Africa too where big brands, usually those with an international outreach, invoke colonialism, visually and discoursively, in their promotional strategies, for example by recalling the aesthetic of primitivism of the early 1900s. Streetstylers seem to be less overtly concerned with positioning themselves within a historical continuum and the post-colonial present. Although in interviews they reference colonialism and express the desire to upturn the visual and epistemological legacy of orientalism, in practice they are creating a Style International that is less burdened with rewriting the past, than with anticipating the future, driving style trends and disrupting the market.

Resources:

Engholm, I. and Hansen-Hansen, E. (2014), “The fashion blog as genre – between user-driven bricolage design and the reproduction of established fashion system”, Digital Creativity, 25.2: 140-154.

Luvaas, B. (2013a),“Third World no More: Rebranding Indonesian Streetwear”, Fashion Practice, 5.2: 203-228.

___ (2013b), “Indonesian Fashion Blogs: On the Promotional Subject of Personal Style”, Fashion Theory, 17.1: 55-76.