TALENTS – THEOPHILUS MARBOAH: “ECHOES AND AGREEMENTS”

Theo Marboah, a student of medicine at Pavia University, has a passion for contemporary African and Afrodiasporic visual culture. I had the chance to hear Theo speak in Palermo at Resignifications: The Black Mediterranean, where he introduced “Echoes and Agreements” (“Echi and Accordi” in Italian), an ongoing digital experiment that uses diptychs to bring together archival images from the Black diaspora and works from the European art canon.

Theo explains that each diptych creates an inter/intra-dialogue that stimulates new ways to make sense of black images and images of blackness. It is also an excellent introduction to black visual art spanning continents and centuries that forces us to reflect on the politics of seeing and un-seeing black bodies. I was not surprised to find out that Teju Cole, himself a photographer, is a fan.

I’m happy to publish Theo’s piece in Talents and look forward to seeing how his project unfolds.

***

“WHAT WE CALL ORIGINALITY IS LITTLE MORE THAN THE FINE BLENDING OF INFLUENCES.” – TEJU COLE

“I DIDN’T BECOME INTERESTED IN IT [THE FORM OF THE DIPTYCH] . I WAS DOING IT AND THEN HAD TO FIGURE OUT WHY I WAS DOING IT.” – LORRAINE O’GRADY

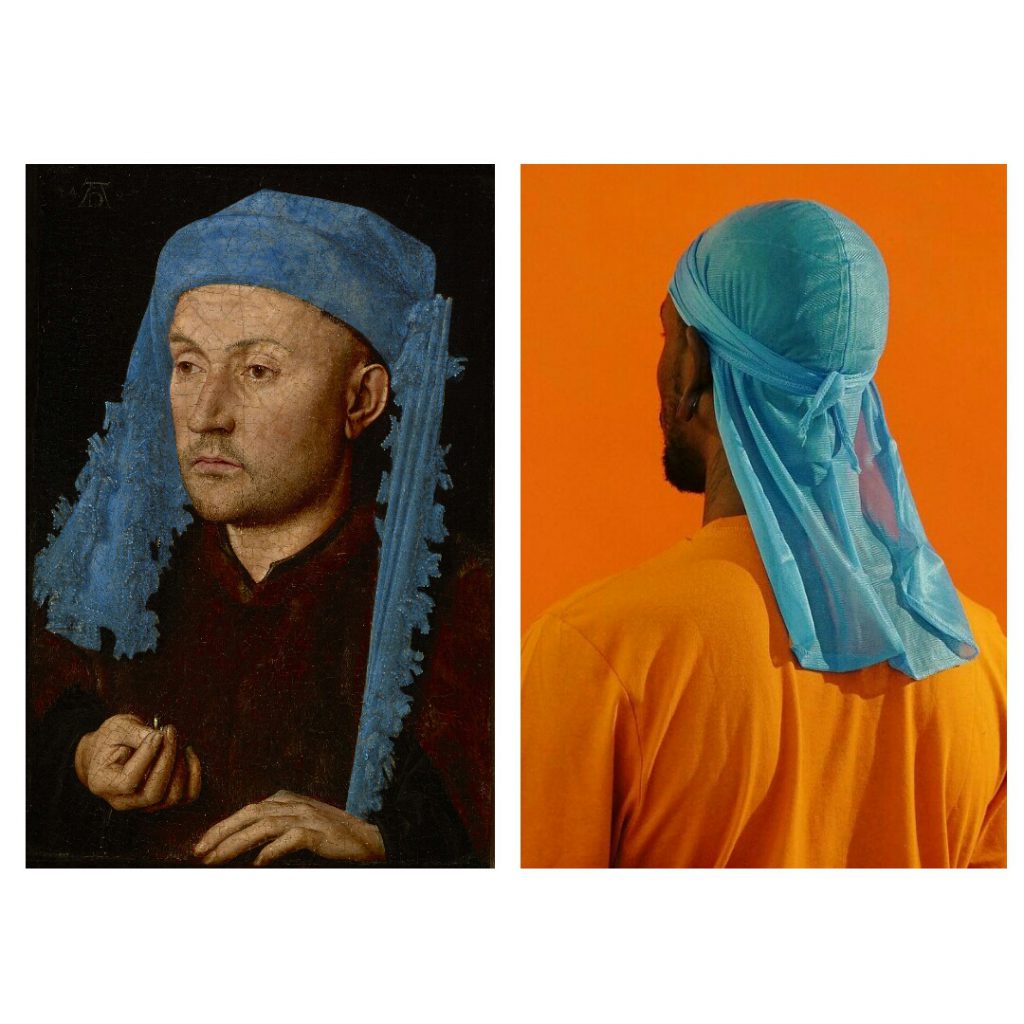

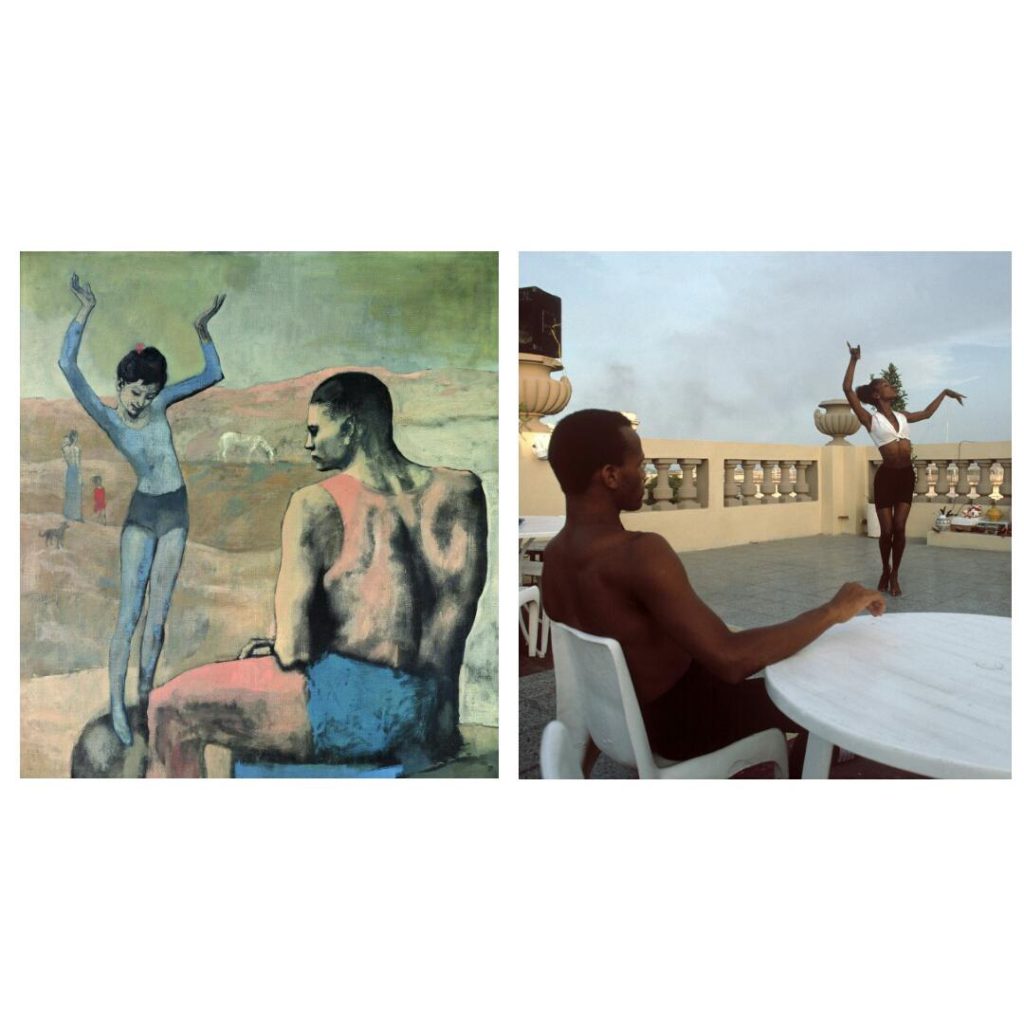

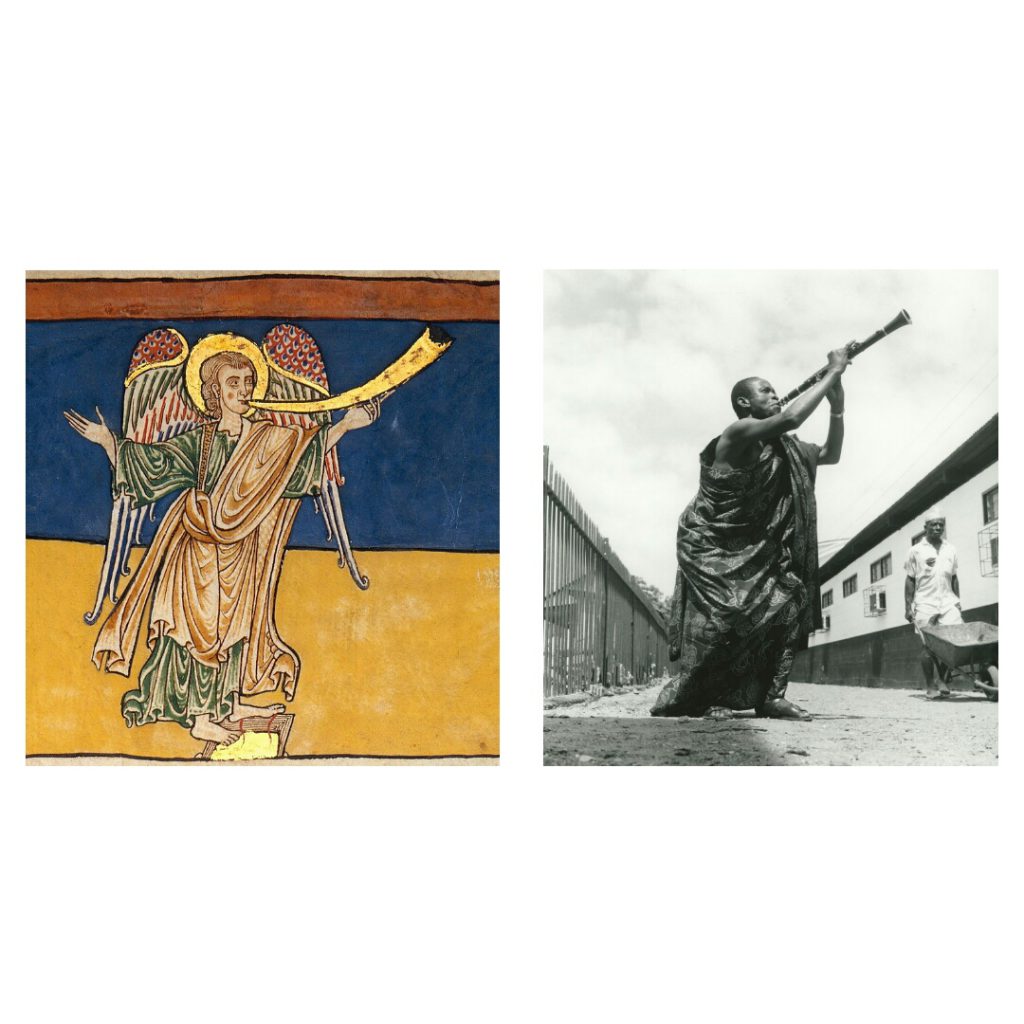

Images are always in conversation with other images. They never stand alone. And they comment on one another unfolding concealed meanings through a visual dialogue. A dialogue that often goes unheard, unless the essential similarities between the images are noticed. These similarities do not only reflect shared experiences between different (groups of) people, they are also metaphor of shared aspirations, desires, and dispositions. Reminders of the category of Universality in which we all dwell, despite the time and space that separate us.

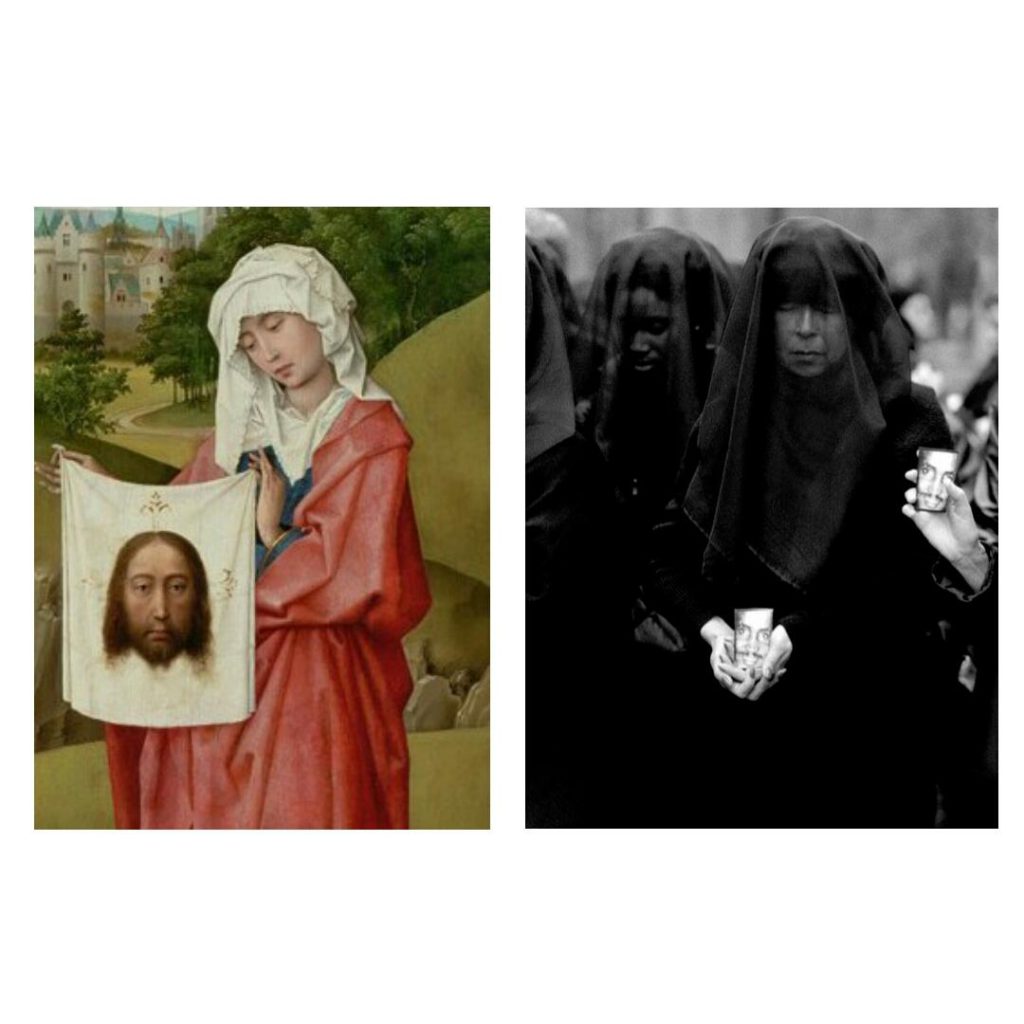

Right. Photograph by Anthony Taylor

Right: Photograph by Shadi Hatem.

The research of these visual rhymes led me to start “Echi e Accordi (“Echoes and Agreements”). A series of diptychs, shared on my Instagram account, that pairs photos from the great Black archive with old European paintings, and juxtaposes African and African diasporic artworks. Each diptych invites new ways to read the images, unveiling new interpretations that words alone cannot accommodate – as the art critic John Berger writes, “Seeing comes before words”.

Right: Rene Burri, Cuba, 1993.

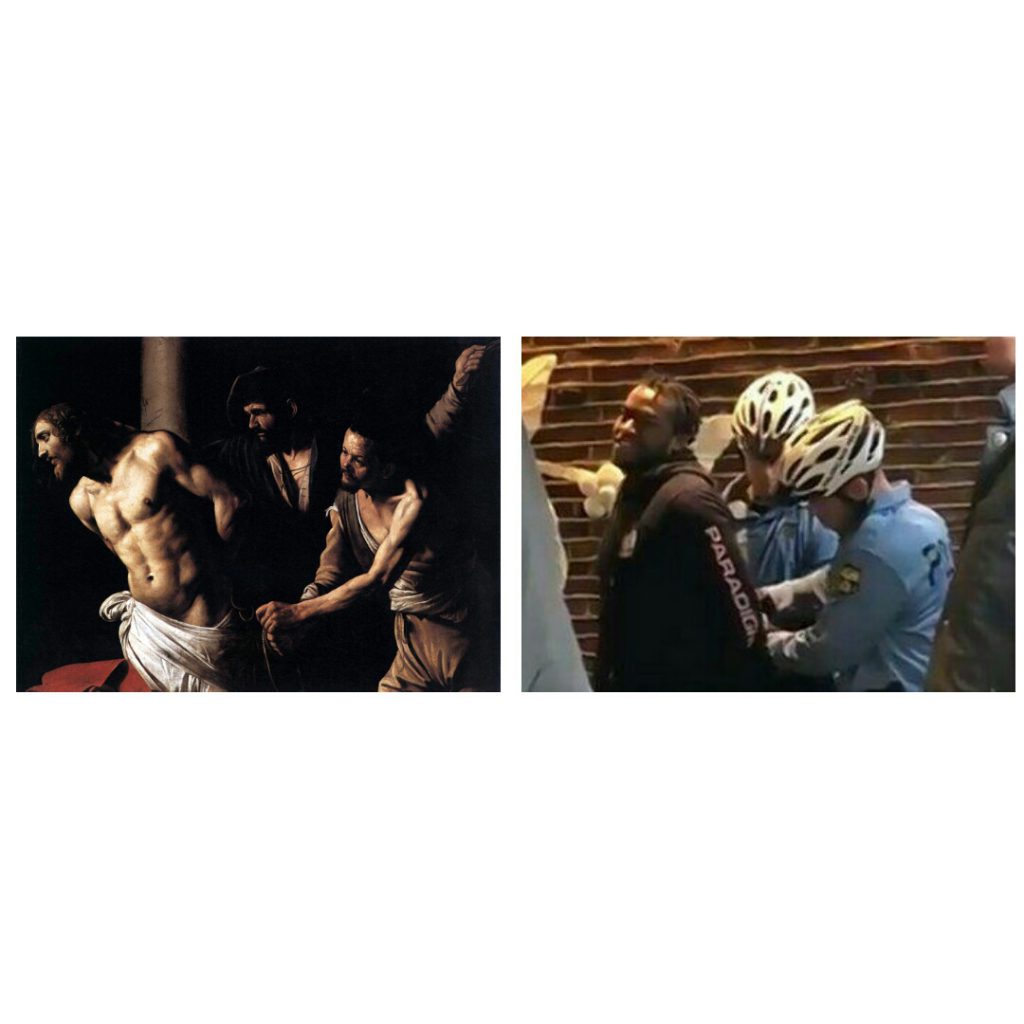

Consider this diptych contrasting a painting by Caravaggio with a still from a video recorded by Melissa DePino.

Right: Still from a video filmed by Melissa DePino

The scenes portrayed are compositionally similar. The figures in the right image almost in unison with the ones in the left. What interests me the most, however, is not the remarkable similarity between the Flagellation of Christ and the arrest of Donte Robinson at a Philadelphia Starbucks. Beneath the superficial analogy, there is another a layer, a deeper layer, that relates the police officers to the perpetrators, Donte to Jesus. I am particularly drawn to the commonality between the latter two: like Christ, Donte is stripped of his humanity, and his body is saddled with uncommitted faults. A synecdoche: the black body pays with its own life sins committed by others.

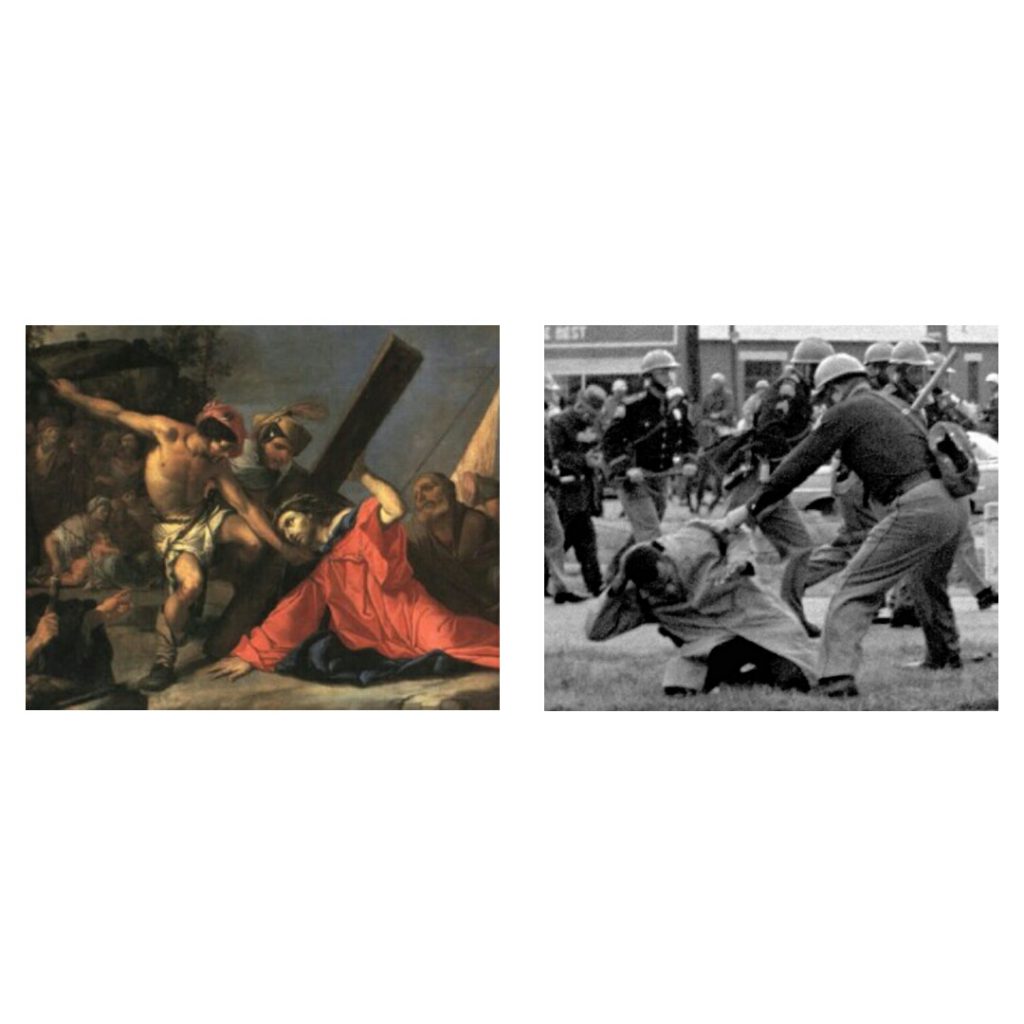

A calvary suffered by black folks living in white terrain. A cross that has been carried since the day our blood “flow like this tide fixed / to the stars by which this ship floats / to new worlds.”

Right: Photograph by Associated Press.

Yet, this Passion has not stopped us from expressing our subjectivity through “words, forms, colours, and action.” It has not stopped us from showing the warp and weft of our humanity – woven as complexly as white folks’ humanity.

But the human is divine, too. And the images created by us, soon after the invention of photography, have been serving to show “God’s image in ebony”.

Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man in nineteenth-century America, understood the great potential of the new medium, and was aware of the democratizing power of the camera. In “Lecture on Pictures”, a speech he delivered in 1861, he said, “What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within the reach of all. The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now posses a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures, could purchase fifty years ago”.

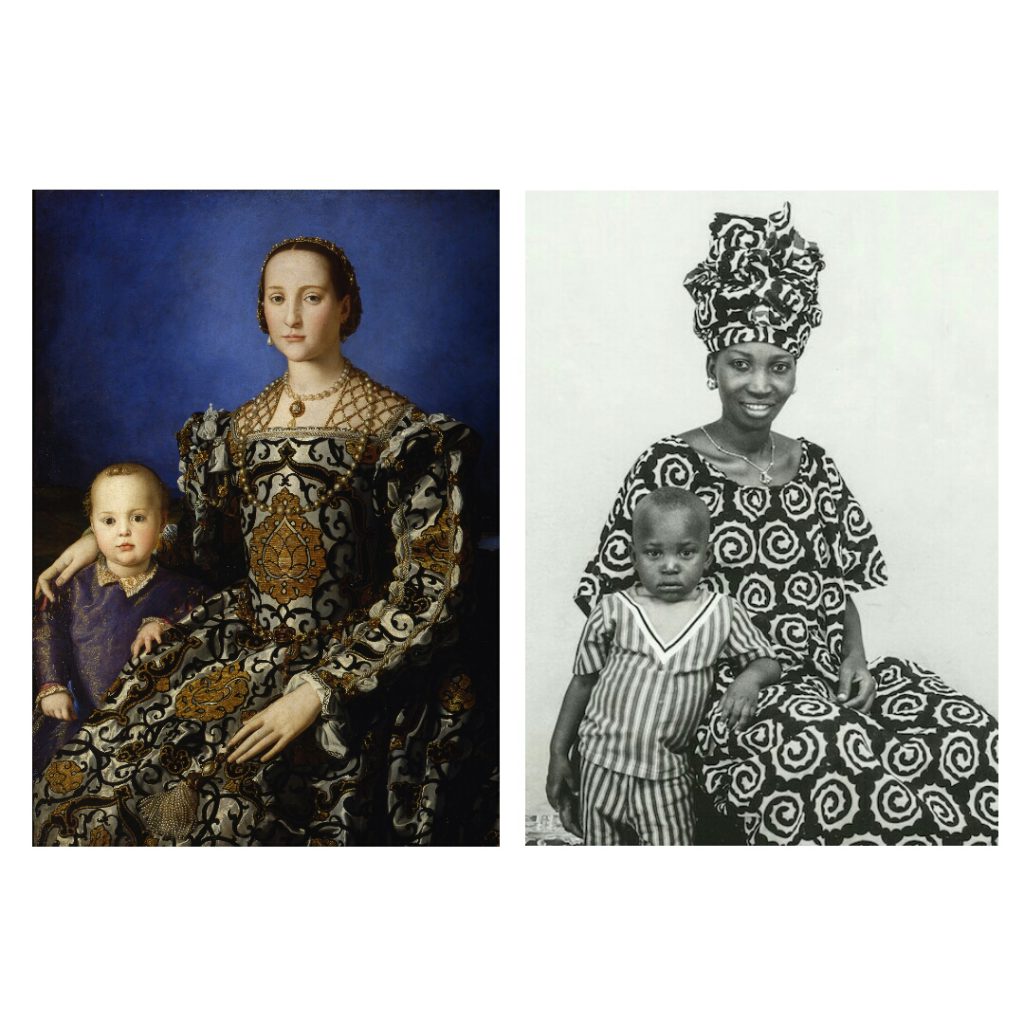

Right: Malick Sidibé, Untitled, 1973

Douglass’ words lie behind this diptych, in which I paired a photograph by Malick Sidibé with the Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo with her son Giovanni by Agnolo Bronzino. The two pictures rhyme with one another, sharing the same melody. A child stands by the right side of his mother. He slightly reclines to the left, supporting his body with his hand and forearm on his mother’s right lap. The mother sits, standing out against the static background which contrasts the dynamic virtuosity of her dress.

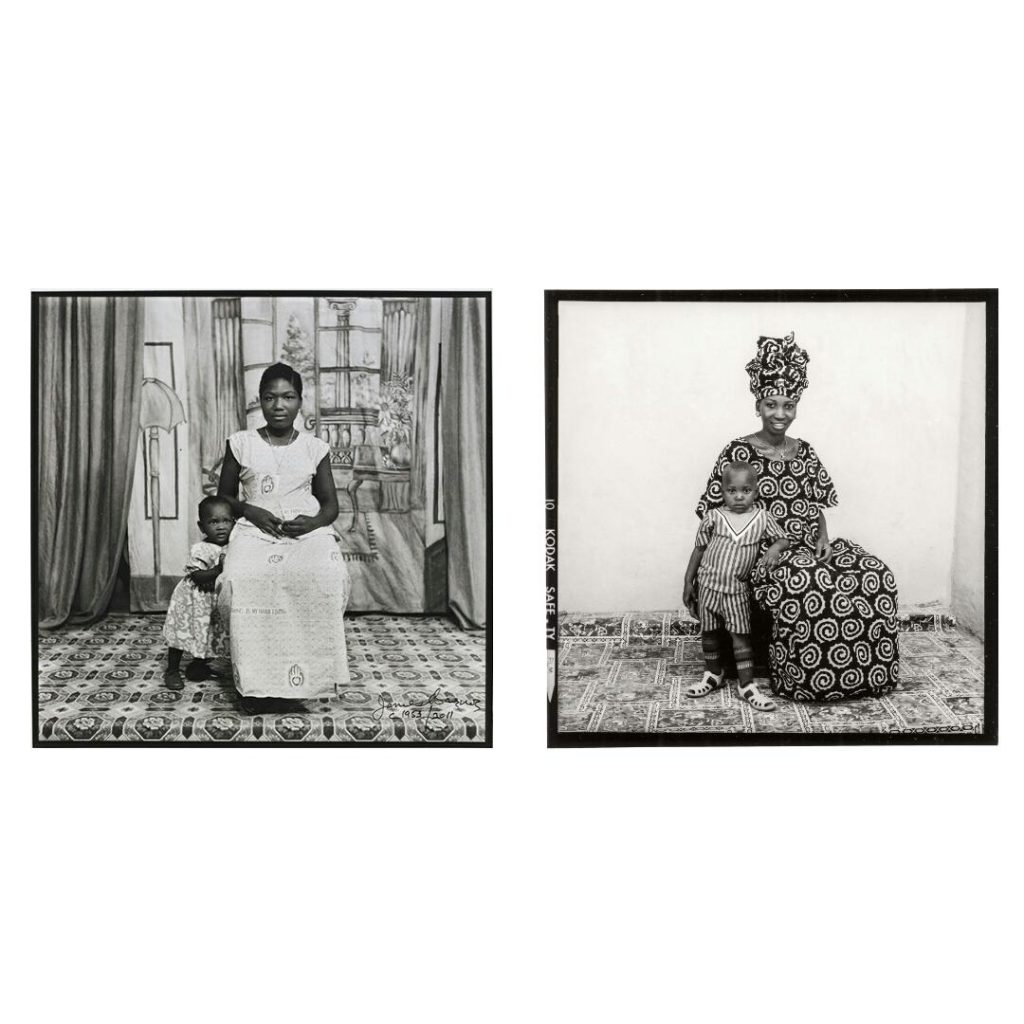

Lingering on Malick Sidibe’s photograph, however, another image comes to my mind. A picture made by James Barnor twenty years before, around 1953.

Left: Malick Sidibé, Untitled, 1973.

The two portraits, in the words of Tina M. Campt, “register as a group”, implicitly introducing “an infinite number of other seemingly identical images we recognize perhaps from our own family contexts.” The portraits, made in Accra at the “Ever Young Studio” and in Bamako at the “Studio Malick”, represented the sitters as they wanted to be seen (“Regardez-moi”), disrupting the anthropological images made by Europeans.

Like the two women, who posed with confidence and pride in front of the camera, we know that images matter – shadows supporting the substance of Black liberation. A constant struggle that is visual, too.

Right: Paul Fusco, Diallo Protest/Women in Mourning, detail, 2000

Right: Daniel Laine, Igwe Kenneth Nnaji Onyemaeke Orizu III – Obi of Nnewi Nigeria

Right: James Barnor, The Legendary Ghanaian Musician E. K. Nyame, c. 1975-76

Right: Photograph by Thomas Prior