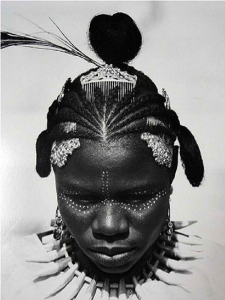

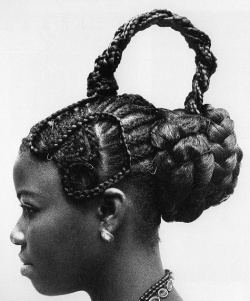

THE POLITICS OF HAIR: J.D. ‘OKHAI OJEIKERE’S PORTRAITS OF NIGERIAN HAIRSTYLES

Today, The New York Times posted the article Hairstyles that Ascend, and Aspire, in Nigeria, about the photographic work of the late J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere. In the course of a career that spanned several decades, the Nigerian photographer, who died a in Febraury 2014 at 83, documented the hair culture of his country, taking portraits of women in elaborate styles and headgear. While most hairdos where popular, others were worn only by the members of certain families as part of a heritage politics based on gendered practices of self-styling (the protagonists of the pictures are all female).

This isn’t the first major publication on Ojeikere; arts centers and several Western media have also featured his work.

This interest in hair styling is part of a larger discourse on beauty standards and appropriation of African visual culture by global media. Months ago, Vogue released a video showing Lupita Nyong’o braiding hair, while hair care and hair styling are a major narrative element in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s latest novel Americanah, something that caught the eye and ear of commentators, since the topic invariably comes up in interviews (like a recent one released by the Louisiana Channel).

Pivotal moments of Americanah take place in a braiding salon in Trenton, U.S.A., while the coming of age of Ifemelu, the main character, is marked, symbolically, by her embracing of natural hair. Ifemelu is a young woman who moves to the States to study, unaware of the racial tensions running through its society. Before the move, she takes blackness as a given and only in the States does she realize the full extent to which her features impose a sometimes unwanted visibility on her. The way she takes care and learns how to control, engage with and manage this hypervisibility are an informed commentary on the politics of appearance of dark-skinned women in the West.

The many scenes set in the salon allow Adichie to touch upon a variety of subjects including immigration, social mobility, gender relations, urban alienation and assimilation. Ifemelu’s choice to grow an afro, something which she discusses in her blog drawing a strong feedback from readers and her friends, show that the divisions of the black community, especially the different perceptions of self of Africans and African Americans. Most importantly, the responses show the extent to which hairstyles are arranged and perceived to be political weapons. Once Ifemelu stops straightening her hair and after she cuts it in “a very short, overly combed and overly oiled Afro”, a colleague asks her: “Does it mean anything? Like, something political?”

Among the other things, Americanah is a meditation on black beauty, which it engages as a dense signifier and hair plays an important part in Adichie’s critique of common assumptions about it. In an interview for Channel 4 she states: “If your hair isn’t straight, people might think that you’re an angry black woman, or they might think that you’re very soulful, or they might think you’re an artist, or they might think you’re vegetarian”. She goes on to state that hair is a powerful platform to discuss and dissects the wider politics of beauty at work in popular culture and their impact on young minds, particularly those of girls.

A bibliographical reference on hair politics is Kobina Mercer, who states that hairstyling is part of the “ensembles of styles” of black people. Talking about the afro, she cautions against its supposed political radicalism. She contends that its naturalness is a myth, it is constructed. “[The Afro] operated on terrain already mapped out by the symbolic codes of the dominant white culture. The Afro not only echoed aspects of romanticism, but shared this in common with the ‘countercultural’ logic of long hair among white youth in the 1960s”. To her, every hairstyle has political potential, in as much as its every instance “seeks to revalorize the ethnic signifier, and the political significance of each rearticulation of value and meaning depends on the historical conditions under which each style emerges”. Most importantly, she rejects the binary opposition of natural vs artificial. Although the political impact of radical hairstyling practices has weaned, “the counter-hegemonic project inscribed in these hairstyles is not complete or closed […] this history of struggles over the same symbols continues”.

What interests me the most of this curiosity about African hairstyling is the fact that, on the one hand hair seems to bring blacks together, on the other ethnicity and geographical provenance make them different. In a review of Americanah published on NigeriansTalk, Blessing Omakwu reports her own experience of cultural adjustment in the States and how it involved hair and race. “I had just gotten a weave put in my hair, and it turns out [my friend] was wondering how my hair had miraculously grown so long since the previous day. I laughed and began to mumble something about the versatility of black hair when an African American female who was sitting across from us fired, “don’t come here with yo’ African self tryna think you black!” It was then that I first realized being American and being African, did not give me a membership card to the African-American club.”

Hello! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!