VLISCO AND THE POLITICS OF AFRO-SARTORIAL GLAMOUR

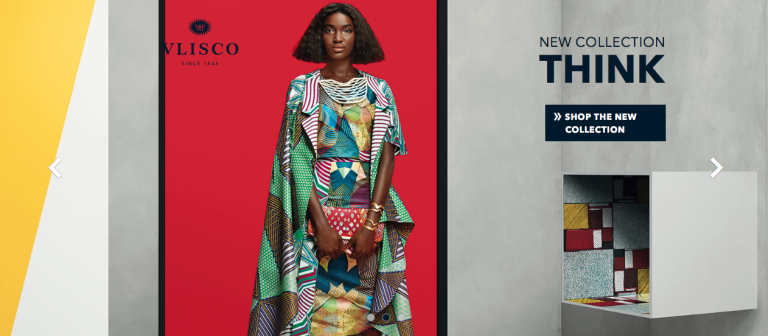

A few days ago, the Dutch textile company Vlisco released its new themed collection of wax-print materials, entitled “THINK”, triggering an outpour of excitement on social media and lifestyle publications. For its first release of the year Vlisco created a motif of lines and geometrical figures whose minimalistic patterns are “inspired by the architectural world of Bauhaus”. The collection’s “clever colouring”, that includes newly-created hues like “grassy green”, is similarly based on the design philosophy of the German school. The effect reflects the company’s signature style that mixes brilliant hues and bold patterns to produce a playful and sophisticated ensemble intended for an audience of affluent customers.

The pictures of Vlisco’s look books always receive consistent attention and are often described as works that fuse fashion and art. As the main interface of marketing and customer captivation, they encapsulate the company’s Afropolitan outreach and cosmopolitan identity as a non-African “design brand which Africans love”. They are, therefore, fundamental in understanding Vlisco’s contribution to the birth and global success of an opulent Afro-sartorial aesthetics and the company’s complicity with endorsing a dynamic view of the continent as a land of plenty.

The pictures for “THINK” capture life-size representations of single ensembles against a white, neuter background. As opposed to notable past campaigns, “THINK” does not employ a flamboyant, artsy, or even theatrical mise-en-scène, but goes for an essential style, which is in tune with the collection’s Bauhaus aesthetics.

Each fashion ensemble is given a name that reflects the message it is supposed to convey. For example, “Think Big” , that pairs a soft jacket and a flowing pencil skirt in an abstract pattern of predominant red and turquoise hues, is about “expanding ones horizons” whereas “Unzipped thinking” , where a fitted V-line top is combined with a tight knee-length skirt in patterns featuring red, green and yellow hues, promotes a sensual “functionality” that “accents your form”. Other ensembles feature slim fitted knee-length trousers with zips in the front, maxi skirts, peplum blouses, and asymmetrical jackets, enhanced by the occasional accessorize.

By clicking on the medium-sized thumbnails on the look book’s main page, the user moves to a dedicated page whose main content is a larger version of the ensemble’s picture accompanied by a short description, a video showing the model in the ensemble turning 360° and thumbnail pictures of its sides, front and back.  The page’s central, “Shop the look” section has clickable pictures of the textiles used for the ensemble which redirect the user to a shopping page. The pre-footer section with the caption “You May Also Like” groups clickable pictures of related outfits. To the right of the main content is a list of utilities including a shopping cart, print and share buttons. To the left are the links to “design”, “fashion” and “article” pages and a search box.

The page’s central, “Shop the look” section has clickable pictures of the textiles used for the ensemble which redirect the user to a shopping page. The pre-footer section with the caption “You May Also Like” groups clickable pictures of related outfits. To the right of the main content is a list of utilities including a shopping cart, print and share buttons. To the left are the links to “design”, “fashion” and “article” pages and a search box.

The interface has an essential design that directs attention to the ensemble’s colorful patterns. Their visually-striking iconography, which changes constantly to keep pace with the evolving taste, visual and cultural language of the continent, has earned the company an unrivaled acclaim in West Africa. While “THINK” features abstract patterns, a look at the company’s catalogue of textiles shows the range of images, symbols, and designs that have been realized throughout the years. The shopping page for “wax”, “super-wax”, “java” and “classics” fabrics lets consumers choose them by color or designs. The designs are further grouped under “decorative”, “commercial”, “nature” and, “objects” categories. Nature includes patterns showing fish, birds, flowers, leaves, stars. In the object page are designs featuring sewing machines, diamonds, umbrellas, mirrors, etc. Vlisco gives names to some of these designs, but all of them are re-named upon arriving on the African market. This act of naming is essential to the marketability of the fabrics, as it ascribes them local significance, contributing to the process of adaptation by which Vlisco has become part and parcel of West African sartorial culture. Nina Sylvanus observes that “[t]he naming process transcends the fabric’s status as a simple object of consumption within the commercial framework.

These names reflect or translate a reinterpretation of the European design patterns [and] can be used as a specialized language” (2007: 210). Wearing a certain pattern delivers a message, builds social ties, or preserves ritualistic function, as when family members and friends of a deceased person are expected to wear matching wax-print fabrics at a funeral.

Furthermore, the set of meanings associated with a design participates in a dynamics of embodiment that is, likewise, essential to the act of cultural translation. Sylvanus continues: “These naming processes, which for the most part relate to contemporary events, allow the fabric’s carrier not only to ‘respond’ to current events or to connect to a particular aspect of global […] culture but also to craft sartorial fashions. The appearance and presentation of the clothed body that the wearing of wax cloth conveys to the fullest draws upon evocative names” (2007: 210).

Indeed, the brief analysis of one of Vlisco’s commercial interface that I sketched above shows that the company’s brand strategy mobilizes a positive idea of racialized and gendered embodiment (Entwistle 2000) to push its commercial aims. Central to the impact of the pictures is the contrasting effect of the textiles against the dark skin of the models. The photographer Sabine Peiper, who worked on Vlisco’s “Delicate Shades” campaign, states that the brand’s signature look is fully obtained only by harmonizing skin and patterns’ hues. As Vlisco specializes in manufacturing and selling yards of high-quality cotton textiles, which it stylizes into outfits exclusively for photographic show, the look book and related pages endeavor to deliver the full range of sensations linked with the experience of being draped in sophisticated fabrics. It is a sensual spectacle that plays on a fabric’s power to evoke memories and create ties. The company’s statement for “THINK” reads:

For countless generations, true beauty and wisdom have been passed down from mother to daughter. Knowledge about heritage, culture, traditions and their love of original Wax Hollandais. This season, we explore these powerful cultural and family ties with Vlisco, which has become such an intimate part of the circle of life in Africa. This journey might well stir nostalgic emotions within you, it’s something we’ve felt ourselves as we’ve delved deep into our extensive archive uncovering hidden treasures of design and stories of generations gone by.

Although the collection themes change seasonally, the pictures always promote a philosophy of femininity, self-confidence, and elegance that constructs blackness as glamorous. Regarded as “the ‘Louis Vuitton’ of Africa”, Vlisco is a fully-established leader of Afro-sartorial aesthetics, probably the best example to cite in a study of cultural encounters through fashion. Of its Afro-sartorial power, embodiment has been a central concern since colonial times, when the company began manufacturing and imposing itself on the local market at the end of the 19thcentury by experimenting with the manufacturing process of Javanese batik cloth. (Click here to learn more about Vlico’s history). Providing an upwardly-mobile class of local administrators and clerks with the material means to distinguish themselves by flaunting a cosmopolitan style, Vlisco has actuated a particular kind of gendered modernization. In this sense, the fashion knowledge and discernibility manifested by the West African women who dressed and continue to dress in Vlisco fabric participate in the instantiation, preservation and development of social practices of power, competence, taste, but also of decency and respectability. “The enactment of respectable femininity and middle-ness hinge on the material support of the fabric, which makes such performances real. Hence the genuineness of the cloth is an essential element in the upholding and reproduction of women’s middle-class values. Embedded in an aesthetic regime of the body, the enactment of such values pushes the boundaries of static ideals of proper femininity. Such performances do not contradict values of propriety and family but they instantiate them as dynamic” (Sylvanus 2013: 38).

So “THINK” is the last incarnation of a century-long history of imperial appropriation, cultural adaptation and neocapitalist colonization spanning North and South, the physical and the digital realms, as well as the dimensions of the perception, taste and self-representation of the people from the African continent and its diaspora. In the context of the “Africa rise” discourse that is reshaping global representations of the continent from land of crisis to land of plenty, it is unsurprising that the company is at the head of an expanding group of neocapitalist ventures willing to make it big in Africa. Its CEO Hans Ouwendijk notes: “Africa used to be known for poverty, for AIDS, for wars, for corruption and all of these negative things,” said Ouwendijk. “Nowadays, Africa is a known for its great opportunity, for its growth — out of the top ten fastest growing economies in the world, 7 are African, so Africa is on a journey that is extremely fast, expanding GDP on an annual basis by 10 percent. It is going to be an extremely interesting market.” He also goes on to praise the cost-effective strategy of the company: “Of a finished design, only a relatively small part of the costs are spent on the wages of the person assembling it.” Maintaining its headquarters and production facilities firmly in the Netherlands, Vlisco employs African intermediaries and retailers to market its products, while keeping the costs of labor to a minimum.

Its brand image, predicated on the allure of cosmopolitanism and fashionability, thus profits from a neo-capitalist principle of exploitation and un-sustainability.

Bibliography and further reading

Entwistle, J. “The Dressed Body” in J. Entwistle and E. Wilson, Body Dressing (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2010), pp. 33-58.

Hemmings, J., “Postcolonial Textiles – Negotiating Dialogue”, Cross/Cultures, (2013): 23-50

Kirby, K., “Bazin Riche in Dakar, Senegal: Altered Inception, Use, and Wear”, in K. Tranberg Hansen and D. Soyini Madison (eds.), African Dress: Fashion, Agency, Performance (London, New Delhi, New York, Sidney: Bloomsbury, 2013), pos. 1684

Klopper, S. “Re-dressing the Past: the Africanisation of Sartorial Style in Contemporary South Africa” in A. Brah and A.E. Coombes (eds.), Hybridity and its Discontents: Politics, Science and Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), pp. 216-231.

Nielsen, R., “The History and Development of Wax-Printed Textiles Intended for West Africa and Zaire” in J. M. Cordwell et al.(eds.), The Fabrics of Culture the Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment (de Gruyter, 1979), pp. 467-498.

Rovine, V. L., “Fashionable Traditions: The Globalization of an African Textile”, in J. Allman (ed.), Fashioning Africa: Power and the Politics of Dress (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2004), pp. 189-211.

Sylvanus, N. “The Fabric of Africanity: Tracing the Global Threads of Authenticity”, Anthropological Theory, 7:2 (2007): 201-216.

__ “Fashionability in Colonial and Postcolonial Togo”, in K. Tranberg Hansen and D. Soyini Madison (eds.), African Dress: Fashion, Agency, Performance (London, New Delhi, New York, Sidney: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 30-44.