#VogueChallenge Africa

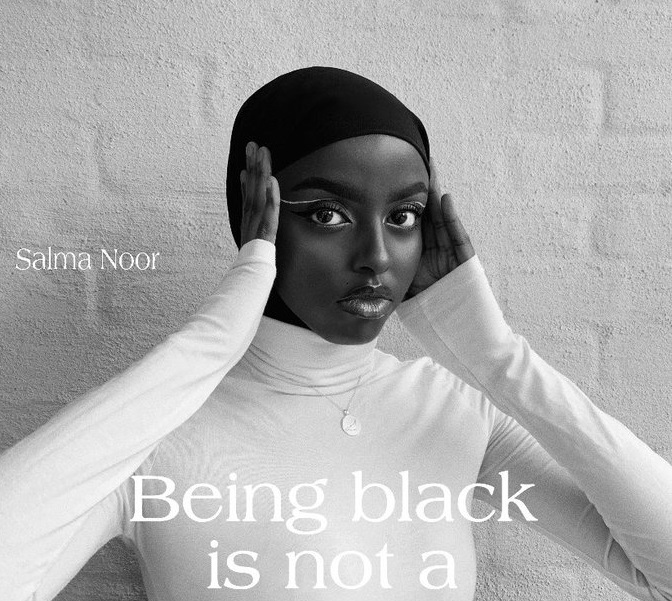

About ten days ago, in the wake of the anti-racist protests ignited by the murder of George Floyd, Salma Noor (@capricornbbyy1 on Twitter; @itssalmanoor on Instagram), an Oslo-based student hailing from Somaliland, launched the Vogue Challenge on social media.

Noor, who is also an aspiring model, created a fake Vogue cover that showed her portrait wearing a black hijab with the subhead “Being black is not a crime”, sparking a viral phenomenon that spread across Twitter, Instagram, and Tik Tok. Since then, she has been featured in Vogue Arabia and on some other platforms, but few articles mention the empowering ethics behind her stunt. Most describe the challenge only as the latest variation on the social media habit of self-promotion and include instructions on how to participate, while taking the chance to link it to Vogue’s recent choice of featuring regular people on its cover.

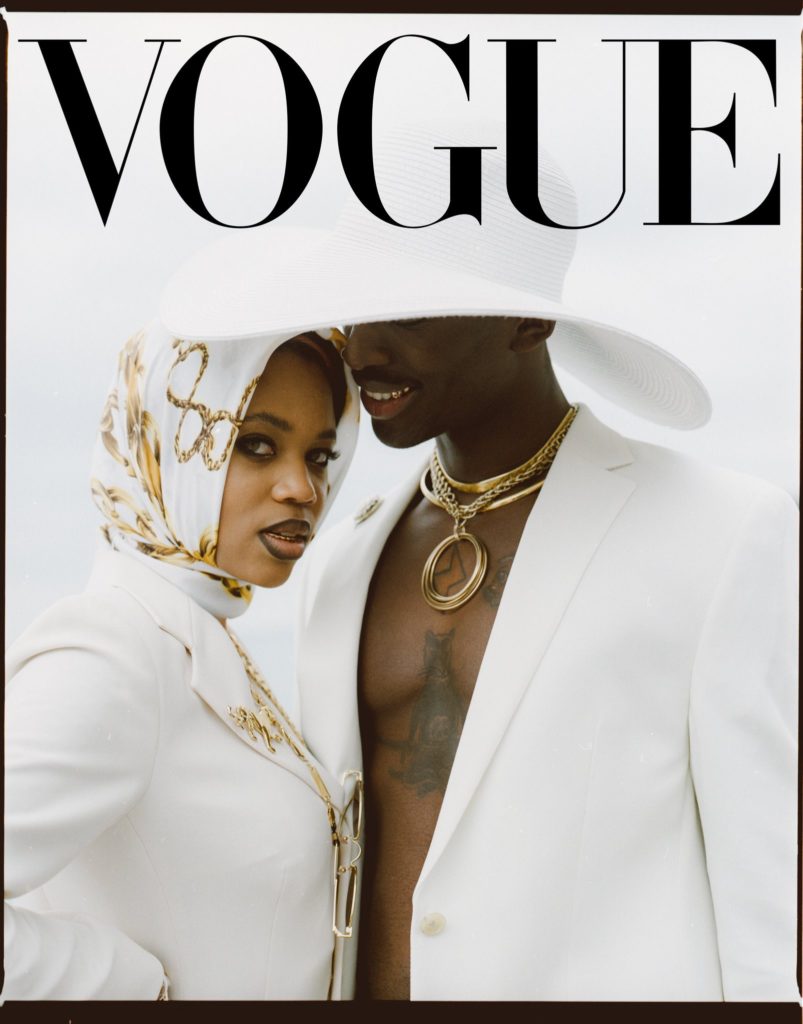

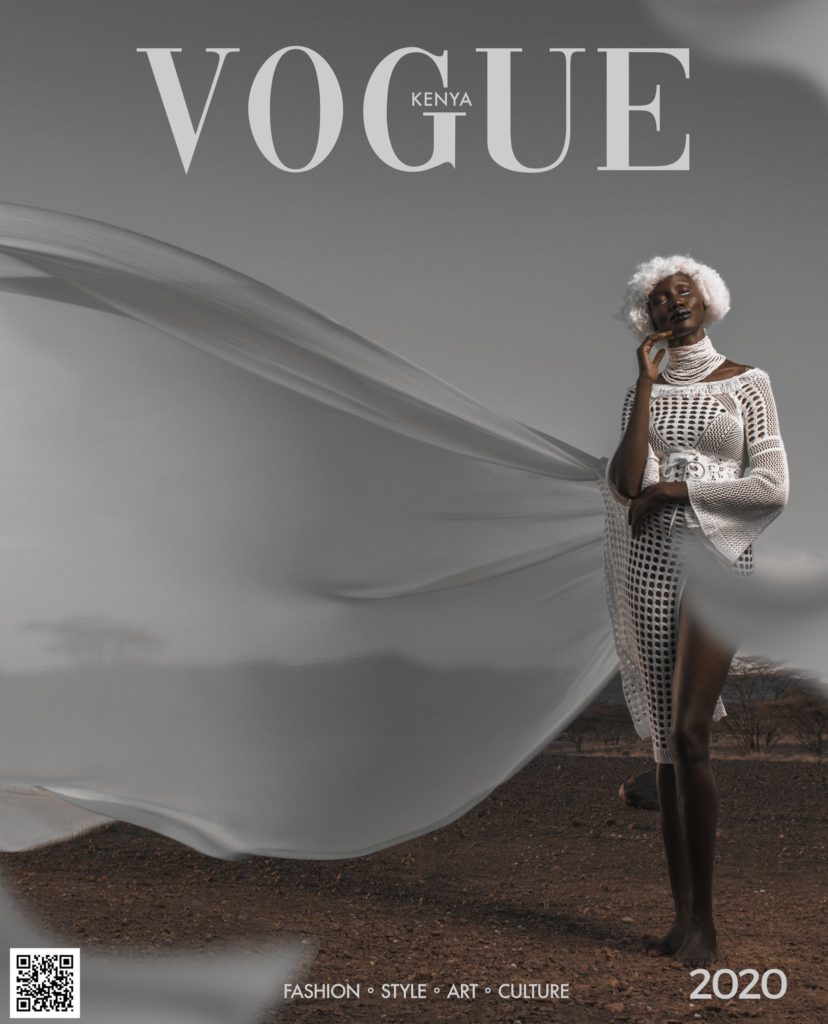

It was image-makers from the South of the world and minoritised communities in the North who amplified the affirmative aspects of Noor’s initiative. Her post targeted the way that mainstream media visually shape ideas of value, worth, and success that reproduce racial and geopolitical hierarchies. Dark-skinned women donning modest clothes are rarely featured on the front page of a major fashion magazine, much less if they are African, this in spite of both the growing market for modest fashion (see Lewis 2015; 2019) and widespread calls to launch a Vogue Africa edition.

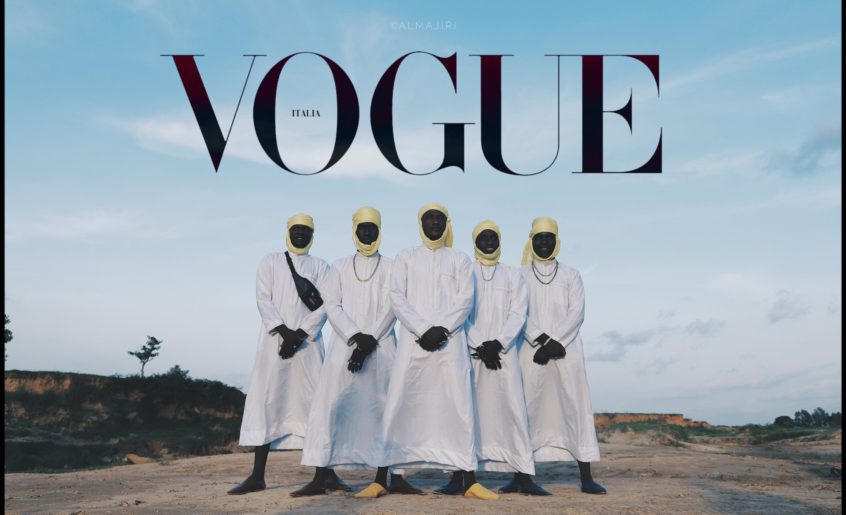

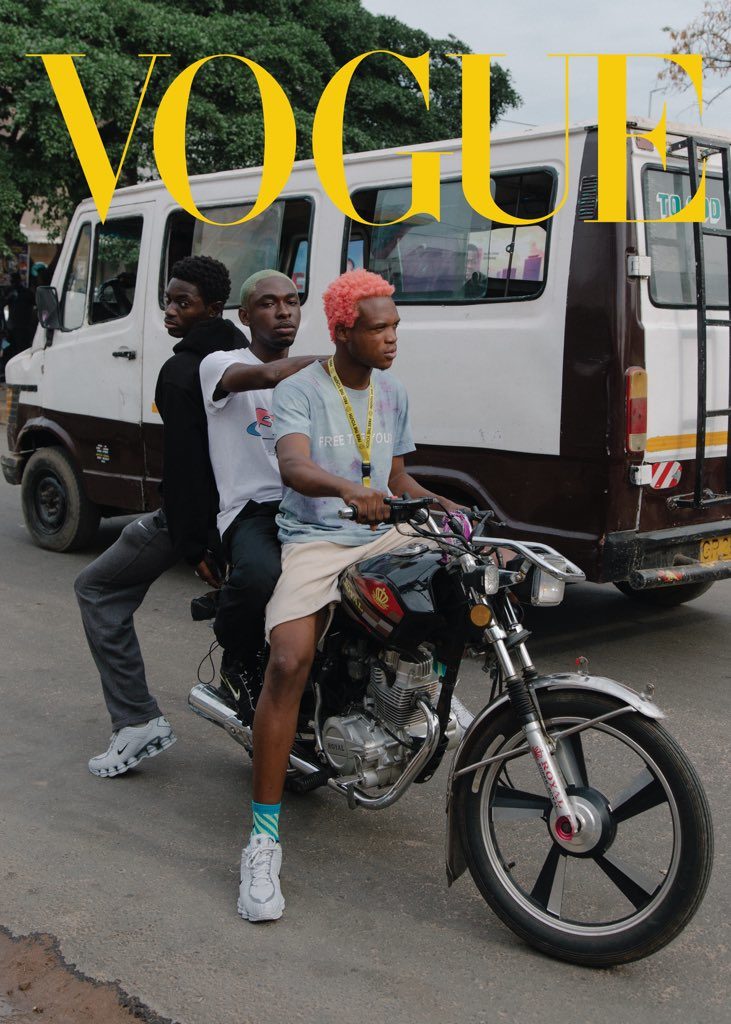

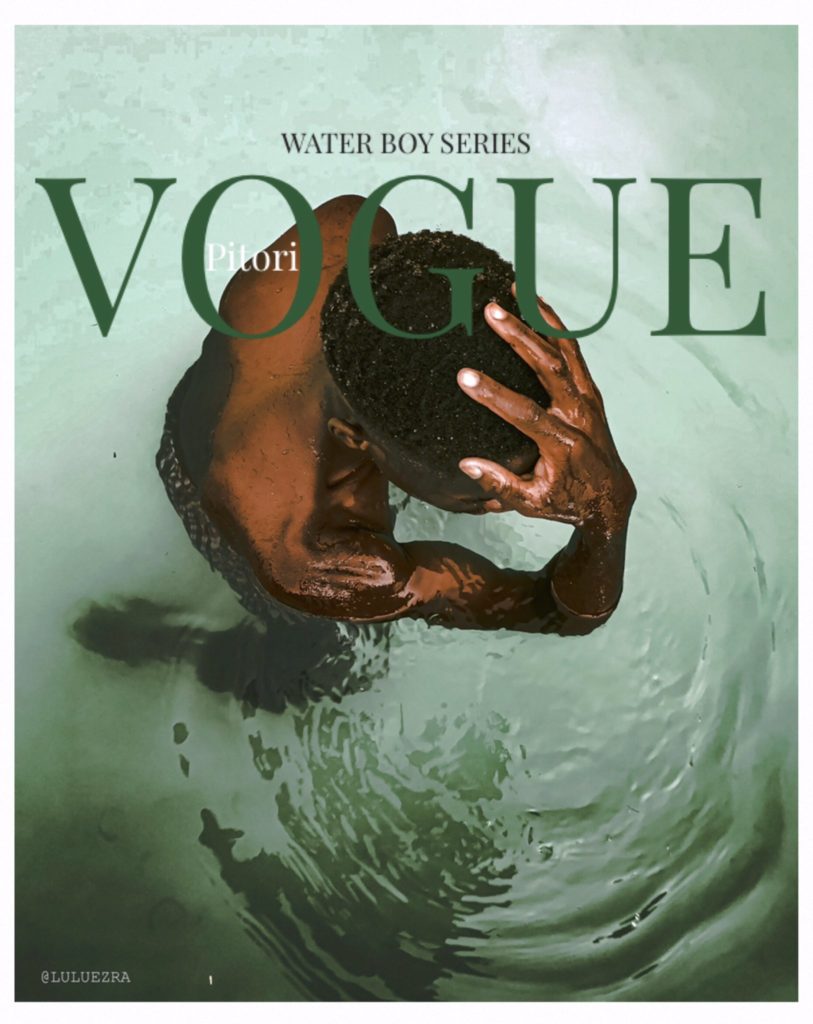

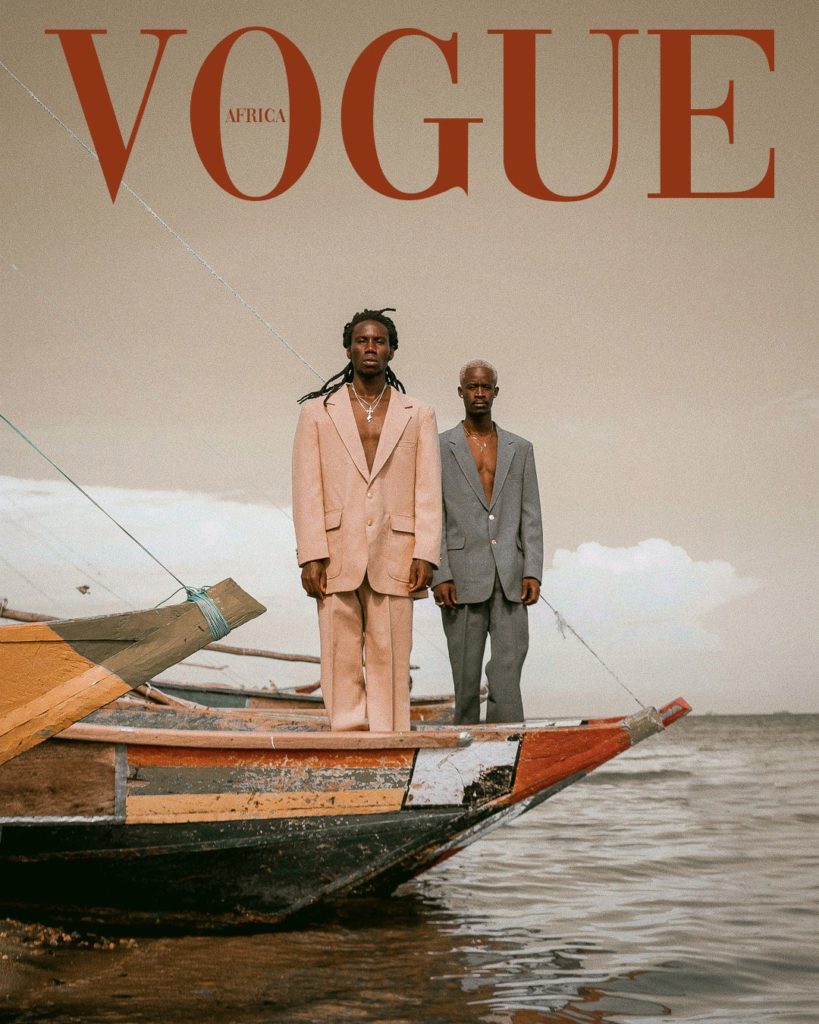

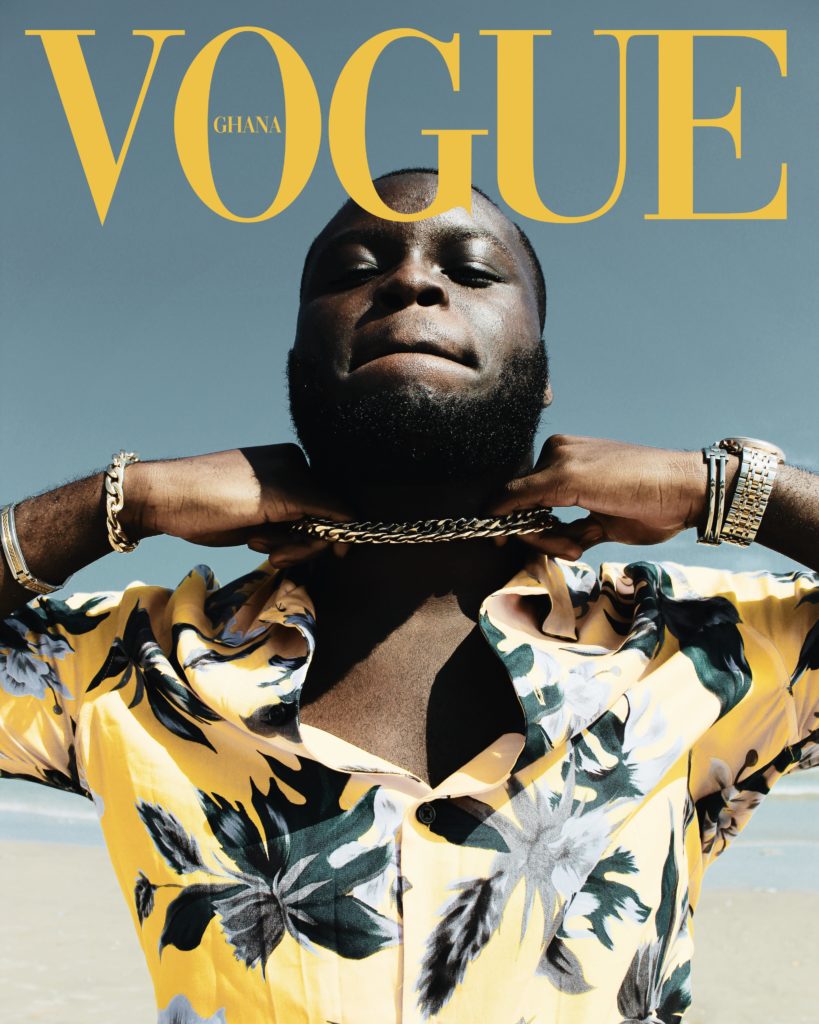

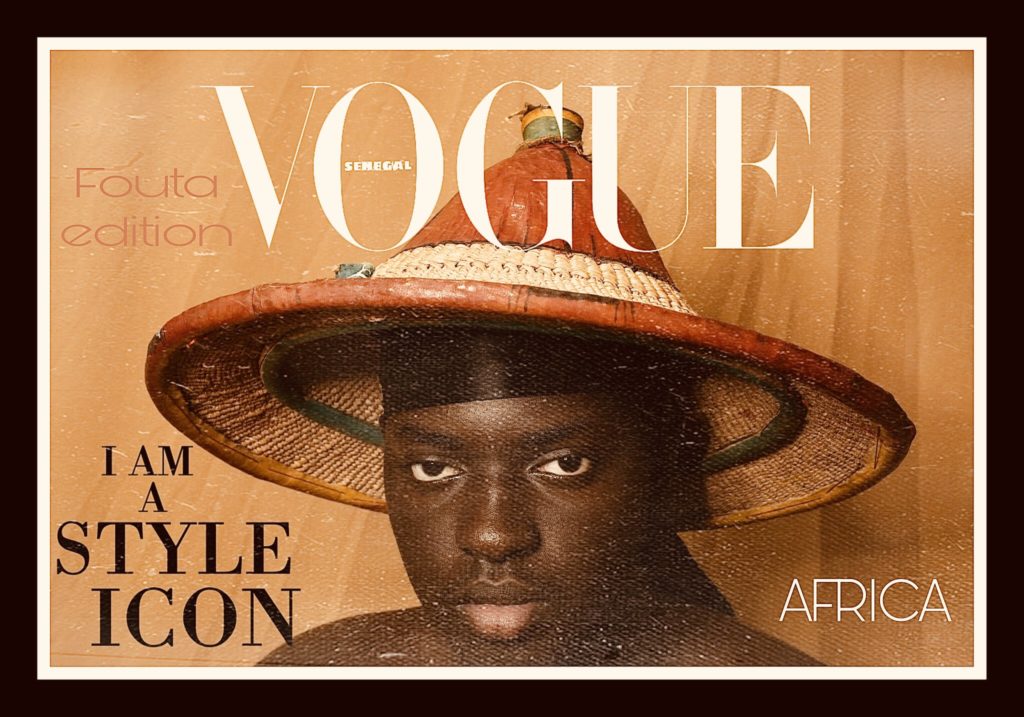

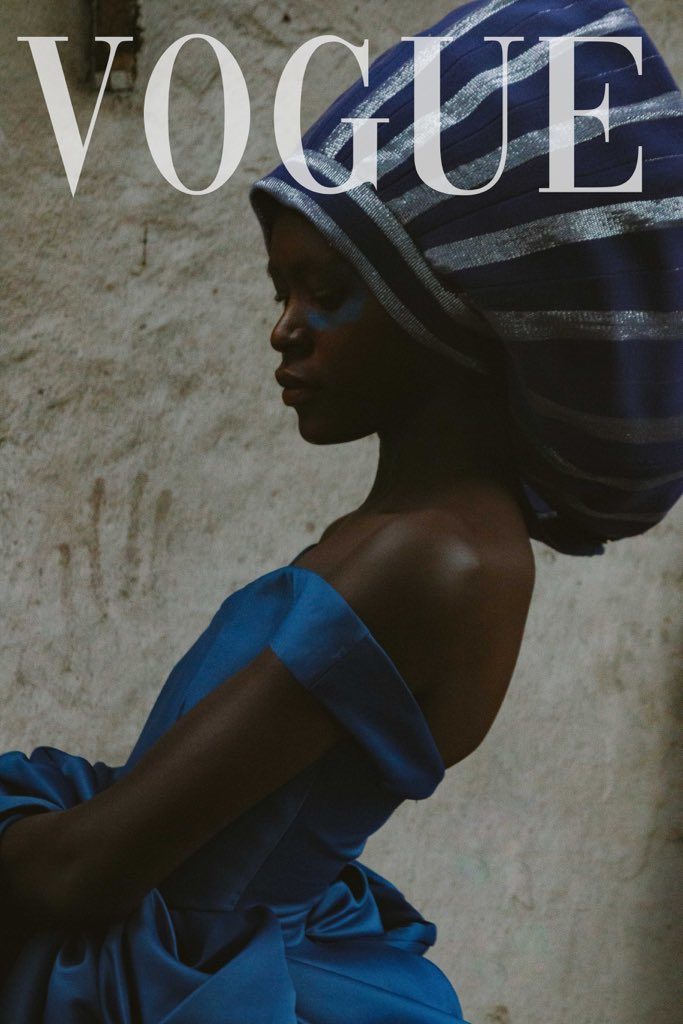

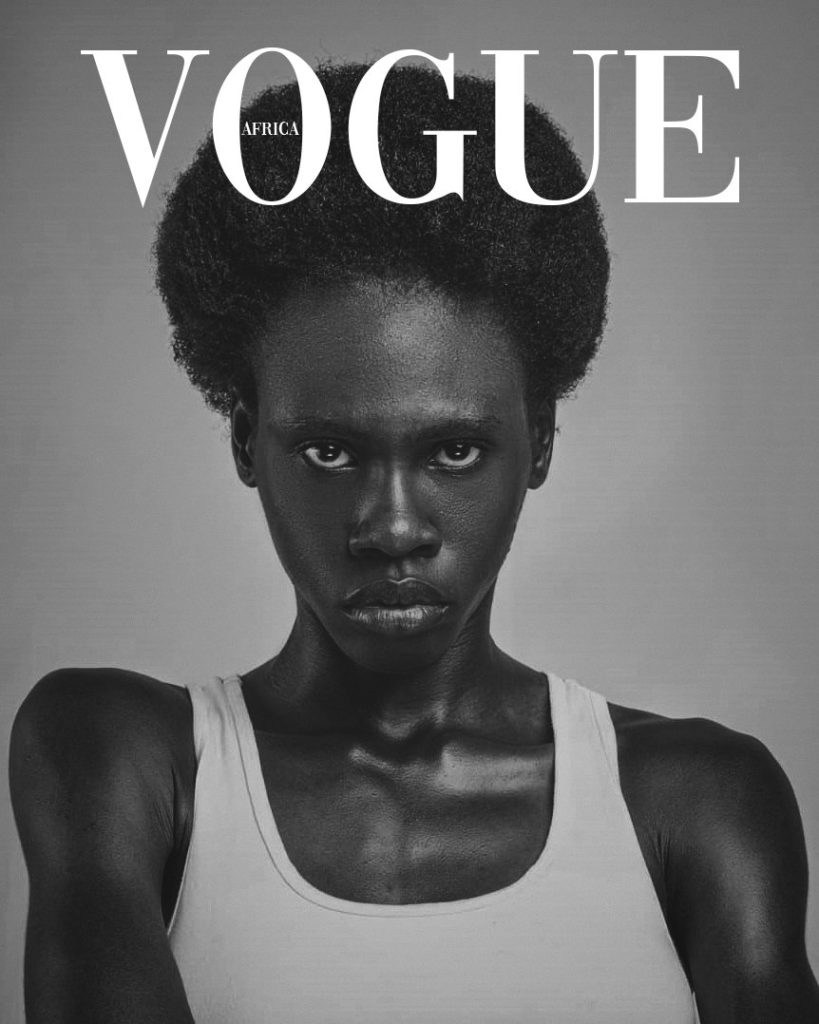

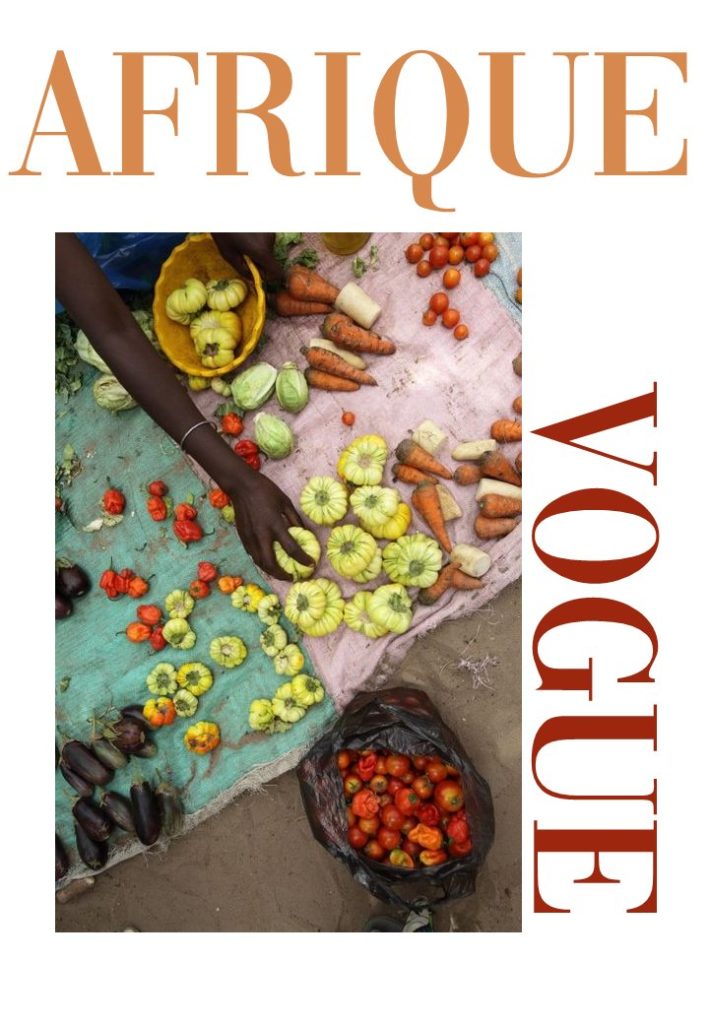

The outpouring of creativity from the continent has been considerable, with regional and ethnic iterations, including Kenyan, Nigerian, Senegalese, and Ghanaian editions.

The users who followed up on Noor’s post include established creatives working to counter the imbalance of visibility for dark-skinned professionals in the fashion world. Among these are photographers Daniel Obasi and Joshua Kissi, and model Oluwatoyin Oyeneye.

In a tweet sharing a selection of frames posted by Africans, Kissi wrote: “The #VogueChallenge is truly beautiful to see. It isn’t enough to have JUST Black models on the cover of Vogue. There should be space for Black photographers to bring these stories to life. In Vogue’s 125 year history there has been one Black photographer to photograph a cover.” Many others demanded recognition for the level of innovation that Africans bring to the sector, calling attention to the intense creative labor that goes into this ongoing practice of self-valorisation.

The iterations of the Vogue Challenge from the continent that I have seen on Twitter follow the semiotic and visual template of Afrosartorialist photography and are immediately recognisable. They typically feature full-body or head-and-shoulder portraits of one or two individuals, highlighting skin color with combinations of lighting and a chromatic palette of pastel and/or vibrant hues. Often the portraits include elements that can be visually indexed as “African”, notably items like fabrics or accessories or backdrops of urban or natural locations. The “feeling” expressed by the subjects and amplified by the artists who keep this conversation on valorising black fashion going, is one of playful agency. The Vogue Challenge offers them an occasion to renew their commitment to claiming active participation in the economy of visual consumption sustaining global fashion, working around modes of gazing that offset hierarchical relationship between the subject and object of the gaze.

Bibliography

Lewis, R., 2015. Muslim fashion: Contemporary style cultures. Duke University Press.

Lewis, R., 2019. Modest body politics: The commercial and ideological intersect of fat, black, and Muslim in the modest fashion market and media. Fashion Theory, 23(2), pp.243-273.

Cover image: #VogueChallenge posted by @_almajiri