Resource alert: SUNU Journal

The first issue of SUNU Journal came out yesterday.

This is a new publication on African affairs, critical thought and aesthetics founded by Amy Sall, a US-based scholar and entrepreneur, whose work focuses on black visual cultures and counter-narratives from the continent and the diaspora.

SUNU, meaning “our” in Wolof, gathers perspectives on black culture and identity by young and emerging voices, with the goal of contributing to the shaping of a post-disciplinary conversation on Africa and its diasporas. The pilot issue contains essays, interviews, poetry, short stories, a section spotlighting a number of photographers, and another on video + film streaming two short movies directed by Melanie Grant.

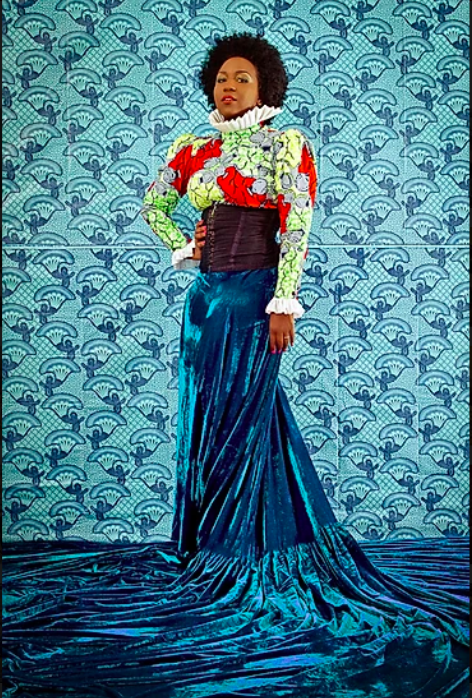

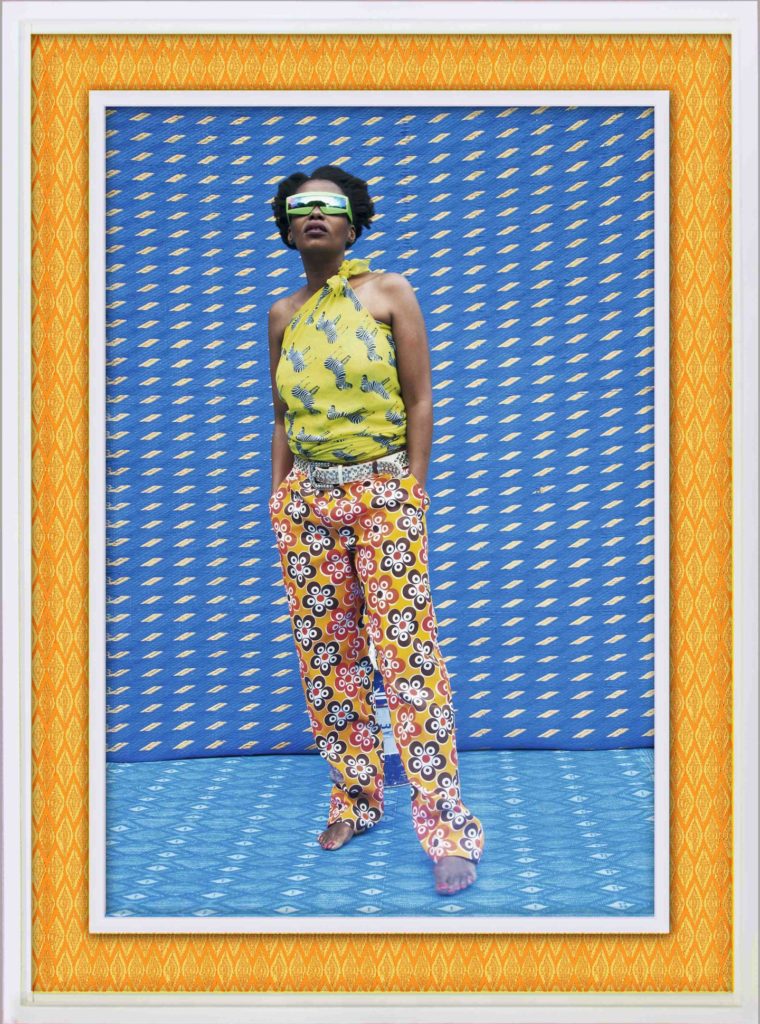

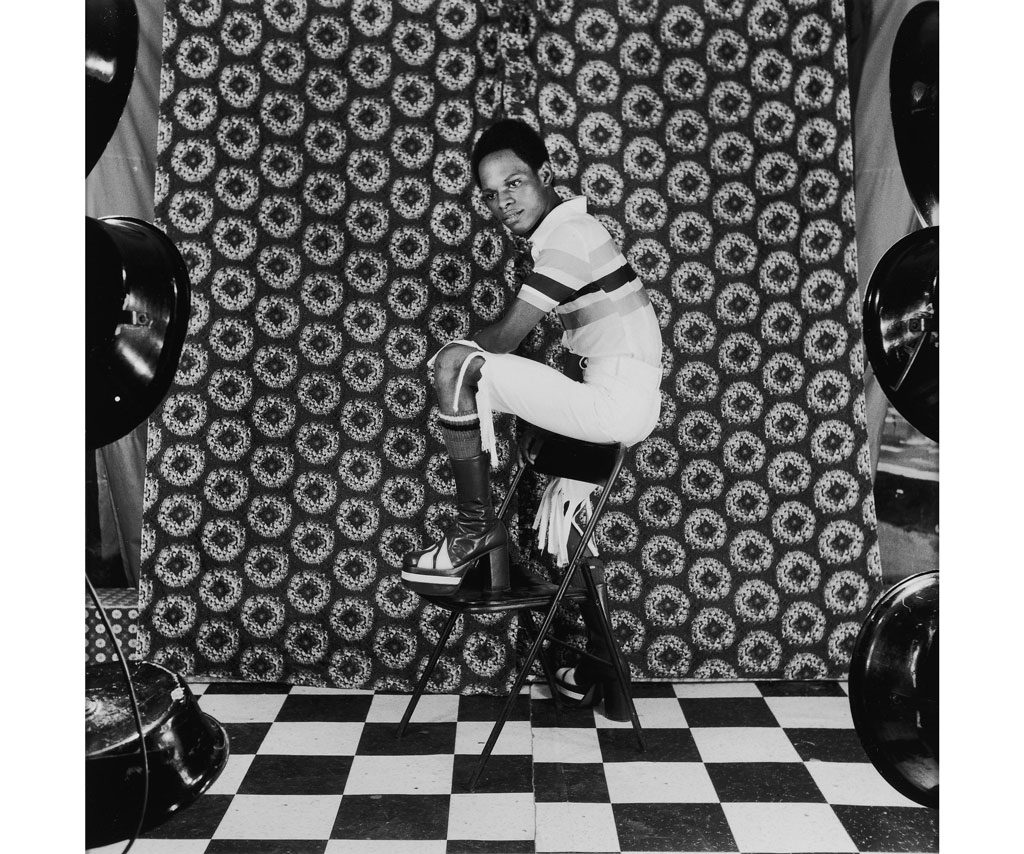

Yayra Sumah contributed a piece entitled “Post-colonial Fabrics in Contemporary African Art”, where she explores how visual artists of the 20 and 21st century used textiles like wax cloth to articulate their African identities in the wake of colonialism. For Sumah, the fabrics channel “the tensions between violence and culture” and the syncretism born out of this encounter.

Sumah studies the work of renowned photographers and artists, including Seydou Keita, Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, Victor Omar Diop, Yinka Shonibare, and Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou, citing anthropological and culturalist studies by Mahmood Mamdani, Salah Hassan, Nancy Hughes, John Picton, and Stuart Hall. She writes that the artists’ use of the fabrics (mostly placed in the background) exposes a processual notion of self-determination, the wax print “signal[ing] the presence of an Afro-modern identity” that shuns essentialism, but remains “within the Western imagination of ‘civilisation.’ The fabrics are visual devices that guide our understanding of the photographed scene and its cultural meanings arising from overlapping flows of signs, goods, and stories. They are also a part of this ongoing conversation on what is African.

Vodounsi Sakpata (Sango Women), 2014

In this respect, whereas fabrics like wax print are wrongly regarded as traditional, what they do is expose the making of tradition as something that is always in the process of being consciously made, remade, and unmade.

“African-ness is not inherent to the fabric, but is constructed when cultural significance is ascribed to forms of representation at different points in history. African-ness is the result of people collectively deciding at a point in time through deliberation, contestation or popularization what to take or leave in a process of cultural exchange and creation. African identity is not determined through the binary of ‘true’ versus ‘false.’”

The final part of the essay looks at the wide use of post-colonial fabrics in contemporary fashion. Sumah observes that they often serve one of two purposes: re-essentialising identity, or lending flair to Western garments. In the former case, claims to ‘indigenous’ or ‘local fabrics’ as truly African assume a culturally-isolated origin. In the latter, ‘African print’ becomes a “one-liner”, where a Western shirt, trouser, dress or suit coat becomes more ‘meaningful’ when afro-centric patterns or accessories are added. Sumah considers both these approaches problematic, as they isolate the fabrics from their context of use and contribution to the aesthetic negotiation of contemporary African identities.

She writes: “In fashion, the attempt to re-essentialize African fabric by claiming autochthony is undermined by the fact that most claims to ‘true’ fabric are not advertised toward masses of Africans, and are not in conversation with the things that are social and culturally relevant to them, neither are they being created using the geometric shapes of older African styles – rather, most newly-designed ‘authentic’ African clothing falls squarely within ‘Western’ modes of dress. The challenge for creators working today is to decolonize and create new frames for representing post-modern African cultural identity without making essentialist claims which seek to negate everything created in the post-colonial era – dismissing it as a simple result of the colonization of the mind. The notion of cultural purity (that is, of African creations ‘untainted’ by Europe or another Other) is in fact itself a racialized and colonial notion. It is not based on the historical experience of practiced belonging or identity on the African continent. Africa has always been a place of movement, trade, syncretism and invention. No innovation has ever been culturally singular.”

Cover image: Vlisco, “The Happy Family/ La Famille” design