DURO OLOWU’S INSTAGRAM EDUCATES FOLLOWERS ON BLACK EXCELLENCE IN THE ARTS

Duro Olowu is known chiefly for two things: a style that mixes prints and textures (dubbed “Prints Charming” by Helen Jennings) and his endorsement by former First Lady Michelle Obama, who also had him decorate the Vermeil Room of the White House for Christmas.

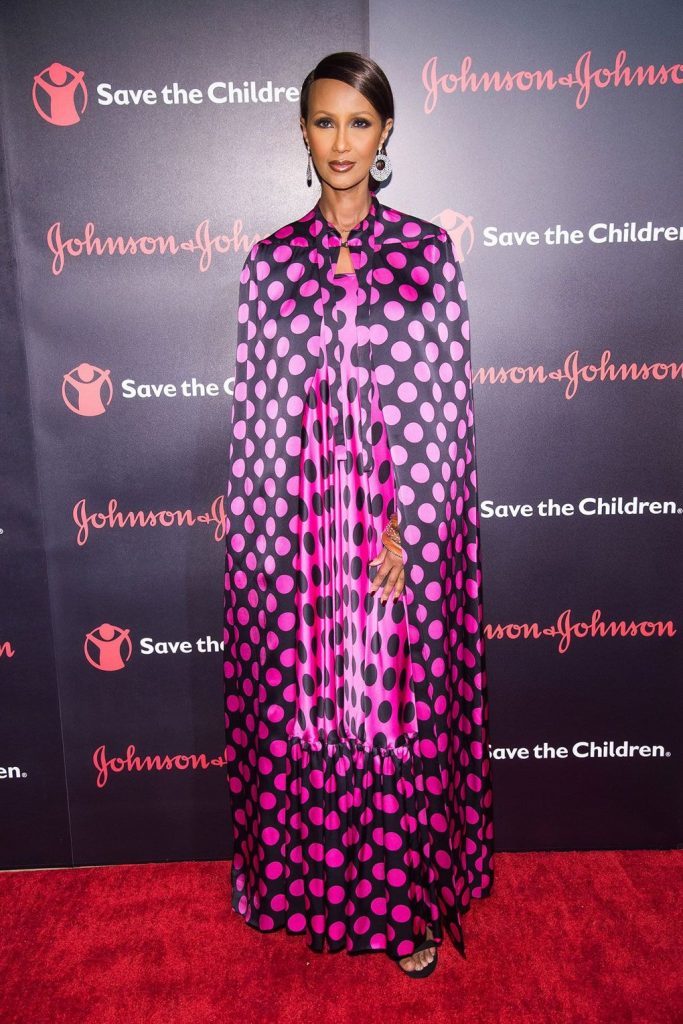

Since establishing his brand in 2004 following an experience with his former wife and winning New Designer of the Year at the 2005 British Fashion Awards, Olowu has been a favorite of celebrities, dressing the likes of Iman, Brittany Snow, Uma Thurman and Iris Apfel. Other acknowledgments include Adele Dejak listing him as one of her favorite African designers.

Born in Lagos by a Nigerian father and a Jamaican mother and educated in the United Kingdom, Olowu is at the forefront of the generation of designers who popularized the Afro-chic trend at the turn of the century, contributing to draw international attention to the continent with styles that infuse local traditions of tailoring with ideals of adornment derived from other cultures. The “Duro dress”, created in 2004, was his first major success, voted Dress of the Year by the American and British editions of Vogue. It has a 70’s silhouette with wide sleeves and knee-length skirt but its most striking feature is what the designer calls “a sort of patchwork of materials, my prints matched with vintage couture fabrics” that has become a staple of his designs.

High-contrast elements and vintage accents, a classic feature of Afro-chic style, make this dress glamorous and playful at the same time. Erin McKean includes it in her volume The Hundred Dresses: The Most Iconic Styles of Our Time (2013) describing it as “a dress about joy. It is impossible to be glum or miserable surrounded by so much vibrant color and so many exuberant patterns. Not only is it physically easy to wear because of its forgiving shape and soft, flowing fabric, it’s emotionally easy to wear too”. Since this breakthrough Olowu’s collage-like approach to fabrics and silhouettes has become synonymous with inspirational and independent femininity and with a certain dislike for fast fashion.

Olowu claims that this compositional mode was influenced by his early exposure to different cultural traditions. In a conversation with Alafuro Sikoki-Coleman for the magazine Art Base Africa he expounds on how his multicultural heritage trained him to look at style as an art practice and a means of social commentary. “The combination of art, cinema, film, music, culture and real life somehow find their ways into each of my collections. A narrative of ideas, and possibilities of clothing and style are always at the heart of my work. I try not to make it too literal; instead, I try to suggest an intriguing reference. My latest Fall 2014 collection ‘Afro Deco’ is inspired by the work of the 1930’s artist and furniture designer Eyre de Lanux, as well as by the colour palette of my friend Chris Ofili’s 2007 painting ‘The Raising of Lazarus’.”

Each collection draws from one or more muses. Notable references are the Hungarian-Indian painter Amrita Sher-Gil, who inspired his Spring/Summer 2016 collection, and the “Montego Bay style” of the Windrush generation of Caribbean women who, the designer’s mother, migrated to England in the 195s0.

This appetite for culture and aesthetics drives the extended research that goes into his design-making and is what makes Duro Olowu stand out as more than a style powerhouse. The designer is an art curator with a vision of inclusivity. “Material”, his first group show held during New York Fashion Week 2012, showcased assorted artifacts from Africa, Europe and North America that included rugs, photobooks, furniture and sculptures placed alongside creations from his current Spring/Summer collection. Among the items on view were works by Photographers Paramount studio of Lagos, David Adjaye, James Brown, and Hamidou Maiga. Roberta Smith wrote a review for the New York Times describing it as “an inspired exercise in cross-pollination and recycling … [a] paradisiacal culture clash”.

A second show in New York, “More Material” (2014), continued the exploration of the links between fashion and art across continents but with a focus on the female body, featuring the designer’s own wares and works by Hassan Hajjaj, Antonio Lopez, Juergen Teller and Rachel Feinstein among others.

Cross-cultural dialogue also inspired “Making and Unmaking”, the group show that took place at Camden Arts Centre, London, in 2016. On that occasion Olowu addressed “the tactile and intellectual processes … and the training that is done by the artists within their own space”, as he says in the interview with Glenn Ligon that introduces the catalogue. Featured artists included Lorna Simpson, Isaac Julien, Neil Kenlock, Grace Wales Bonner, and Irving Penn.

This show looks at the works, but also at what makes them visible and valuable. It brings out the artists’ concerns with how their approaches to identity, sexuality and the representation of the body are perceived and presented. So, in a way, it is a meta-discourse on art-making that focuses on context as much as on “text”, that is, on the art object itself. By focusing on the conditions that make art possible and necessary, it also refers to the limits and negotiations that go into this practice, including the difficulties of making art as black artists.

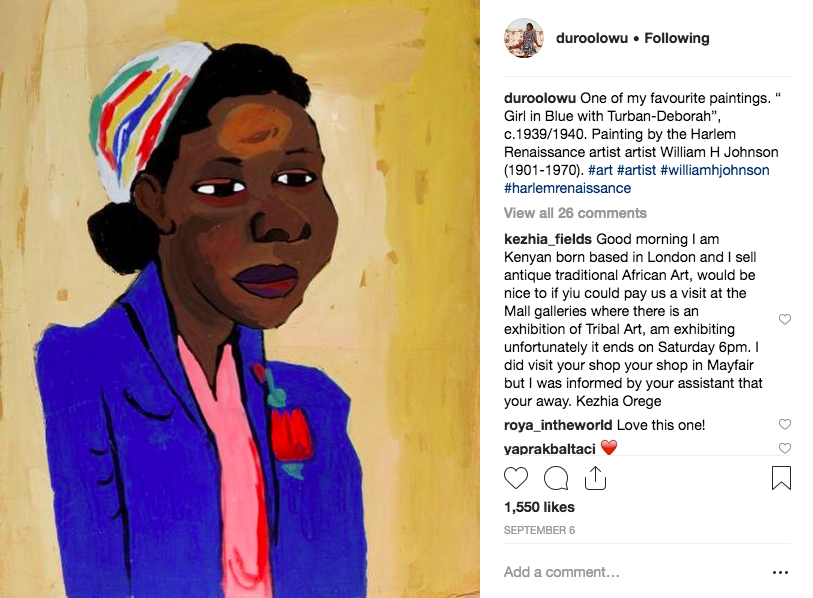

Olowu pursues this investigation also on social media, particularly on Instagram where he shares information and visual material on what inspires his artistic practice. His account is a digital sketchbook and moodboard that, while spanning cultures, eras, and continents, privileges black visual culture and black excellence in a way that I cannot but interpret as politically-charged. To my knowledge the designer has never posted anything that directly references politics, but the way he foregrounds achievements by African artists and artists of the diaspora from the fields of painting, sculpture, popular music and performance is itself a political gesture that makes visible a tradition that, save for some exceptions, has never been enjoyed mainstream levels of attention and criticism. Doing that outside of the walls of art galleries makes this research accessible and meaningful to a wider audience that might not be necessarily interested in either luxury fashion or art-making.

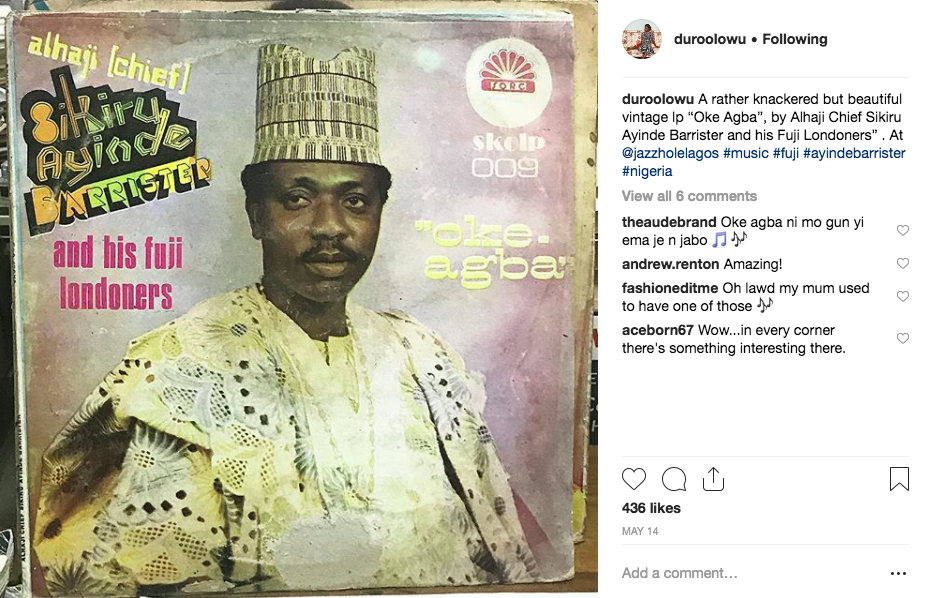

In the interview for Art Base Africa he lists the personalities that he looked up to as a teenager, describing them as exemplary most of all in the way they presented themselves. “Musicians like Mriam Makeba, Fela Kuti, Sunny Ade, Jimi Hendrix, Victor Uwaifo, Davie Bowie, the Wailers, King Sunny Ade, The Lijadu Sisters, Marc Bolan etc. were also very inspiring to me not just musically, but because of how they put themselves together. I treated their album covers like paintings.” These celebrities made up an alternative visual canon that catalyzed otherness and blackness as identity positions to flaunt and reclaim. Their very existence was a form of art making that taught the future designer an idea of beauty that was not universal, but situated and derived from specific historical, geographical and cultural circumstances.

Today Olowu pays homage to them on Instagram and in his curatorial and design practice. His aim is to engineer a kind of visual layering that reconfigures how we see race and beauty.

Extracted from the art gallery, these images circulate on social media. As they are pinned, shared, reposted and commented they contribute to diversify our global visual regime while establishing fashion’s social commentary and value as a means of education.

Cover image: Duro Olowu’s collection of Yoruba buba tops dating 1920s through 1970s