YAGAZIE EMEZIE IMAGES IGBO CULTURE FOR VLISCO

Last month Vlisco&Co unveiled a multimedia project on Igbo culture that includes a collaboration with artist Yagazie Emezi and designers Fruche and Gozel Green. In “Present and Forgotten – An amalgamation of Igbo culture ” Yagazie revisits a topic that is dear to her heart: preserving Nigeria’s ethnic memory and knowledge. For Vlisco she created a series of shots of culture-sensitive styles that highlight aspects of Igbo lifestyle and traditions.

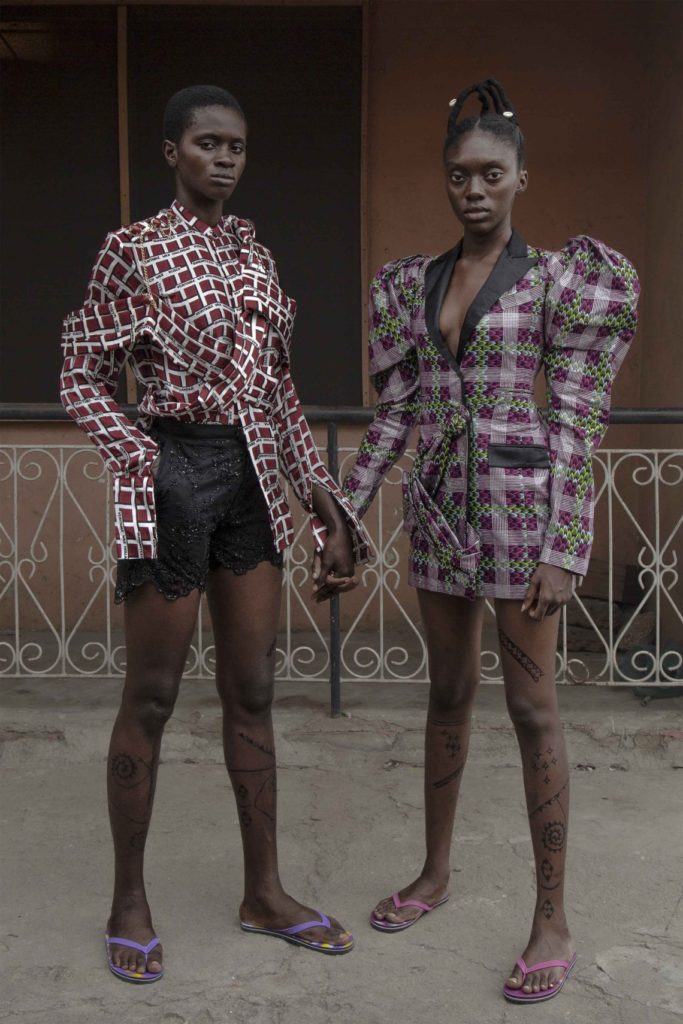

Her lens captures women holding hands and applying paint on each other’s bodies. Their body language is intended to shed light on same sex-unions in pre-contact Igbo culture. Before conversion to Christianity, a childless woman who experienced the death of her husband could elect to marry one or more women. If she wished to have children she would choose a man to conceive and then raise the offspring with her wife-husband, who would give the baby her name.

The models have symbols painted on their arms and legs. The designs, called uli, are the second element of Igbo culture highlighted in the lookbook. Now almost extinct, this form of feminine cosmetic art (uli means decoration) used natural dyes (extracted from charcoal, clay, soil, plants and tree bark) to make monochromatic patterns on women’s houses and bodies for events like funerals and title takings. Uli could have a ritualistic or decorative function and were inspired by experience. They could be abstract or represent animals, plants, celestial bodies and everyday objects and would last about a week. In this article Angela Udeani describes the design as a ” curvelinear, calligraphic visually precise, space emanating and greatly elemental art with high romantic appeal and culturally implied symbolism.”

As Igbo culture associates beauty with morality, uli was widely practiced throughout Igboland until it declined following a ban by the British who deemed it primitive.

Uli inspires the two collections commissioned by Vlisco. Gozel Green’s “Uli Art” employs fabrics with original Igbo designs in a modern “mix of cuts, trims and lines to emphasise the body form of the woman.” Fruche’s “Reincarnation” celebrates the “hardworking and progressive” nature of Igbo women with dramatic shapes, voluminous garments and unconventional designs that imagine colonial Igbo women of the future.

Fruche and Green promote Vlisco’s philosophy of fashion that is respectful and proud of African cultural heritages. The exploration of Igbo lost customs and artistic practices expresses “Vlisco&co”‘s specific mission of creating a space for African artists to “explore the future of African print”. Another recent example of this approach is the “New Traditions”campaign shot in Benin Republic and released in August of this year that showcased the aso-ebi tradition, where members of a family or even entire communities show solidarity by wearing outfits made of the same fabric.

In both instances the designs, locations, and overall “atmosphere” of the works feel authentic to the target market and are in line with Vlisco’s commitment to the idea of an inclusive modernity that champions diversity, while retaining a contemporary appeal.

But compared to the glamorous Benin shooting, the Igbo lookbook consciously plays against the conventions of fashion photography. Yagazi, whose documentary work concerns African women’s relationship with their bodies, introduces critique and self-reflection, taking the focus partially away from the fabrics and the garments to highlight the history and stories that inform her vision.

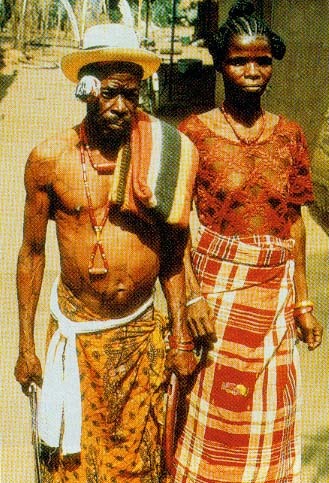

In “Present and Forgotten” she pursues her aim of counteracting visual stereotypes about. Africa and Africans by referencing the aesthetic tropes of colonial portraiture and turning the gaze back on the photographer. On her website she writes:

as I stared at those old images, I saw the often furrowed brows, the angry eyes. There are records of foreign ethnographers capturing ‘specimens’ to photograph, of individuals and families being summoned and posed. Could they say no? Did they want any part of it? We have not forgotten. In this story, I am once again, an invited guest. The stare of the couple is meant to challenge and acknowledge. They say, – You are here because WE ALLOW it.

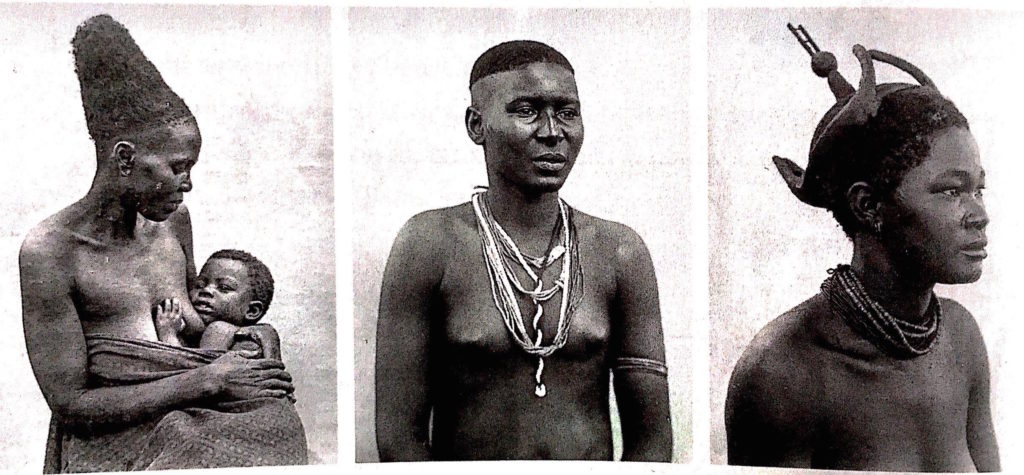

Here Yagazi calls attention to the visual regime of stasis and tension that is the subject of Tina Campt’s essay “Striking Poses in a Tense Grammar: Stasis and the Frequency of Black Refusal” included in her latest book Listening to Images. Exploring the Duggan-Cronin 19th-century archive of ethnographic photos of rural Africans in the Eastern Cape Campt notices the women’s “stillness”, which has been read as an aestheticization of “authentic” native culture. But she contends:

These are not women frozen in time or by the camera. Their taut demeanor is an active, tense, and expressive practice of both restraint and constraint. Each of them appears to hold back, hold in, or keep something in reserve – in preparation or anticipation of something to come. The muscular tension they display is an effortful balancing of compulsion, constraint, and refusal that vibrates unvisibly yet resoundingly through these images. (57-58).

The tension running through these bodies is a physical reaction to life under colonialism and exploitation. Yagazie puts this silent grammar at the forefront of her work for Vlisco, a company that is implicated in this very system of power on multiple levels: as a venture selling designs made with techniques that were developed to dress its colonial subjects, and as a brand operating in a neocapitalist and neocolonial system that still runs on exploitation.

That Vlisco chose to support her aim of “creating works that are truthful and layered” is an interesting strategy that, while capitalising on the critique of the system, leaves also space for further critique.

Bibliography:

Campt, Tina M. (2017). Listening to Images. Durham & London: Duke University Press.