READING FILES: CRITICAL ARTS, “(RE)FASHIONING AFRICAN AND AFRICAN DIASPORIC MASCULINITIES” (PART 1)

Stylin’ cannot be separated from [its] cultural roots or, indeed, routes – Checinska

The journal Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies dedicated an issue to male self-fashioning in Africa and the diaspora. Edited by Leora Farber, the issue features articles that span South Africa, the Caribbean, the US, and Britain, shedding light on the under-investigated topic of black male style.

Farber, who is Associate Professor at the University of Johannesburg where she directs the Visual Identities Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), introduces the issue in the opening article “Assertive Creative Agencies through the Sartorial”, describing male self-fashioning as a form of radical imagination. Citing Anthony Bogues’s concept of “agencies” as practices of freedom enacted in daily life, she contends that male “style-fashion-dress” (a terms borrowed from Carol Tulloch) allows African men to act creatively and draw from their experiences to express their sense of self and, in the process, accrue power. In particular, Farber refers to the sartorial performances discussed in the issue as “black dandyesque modalities”: “a means by which self-/gendered/racialised/sexualised identities and subjectivities can be imagined, (re)defined and/or (re)produced”. Monica Miller’s and Shantrelle Lewis’s research on black dandyism and Homi Bhabha’s conception of “mimicry” are the studies Farber references to explain how sartorial performances help African men make sense of “shifting notions of black masculinity” and navigate multiple cultural references, histories and systems of power, finding power in fluid and ambivalent modes of self-display. Ultimately, Farber invites readers to look at the case studies collected in the issue as practices of “nuanced” resistance that, while not necessarily pursuing active protest or defiance, “denote forms of disrupting, dislodging, and troubling hegemonic and/or normatice codes”.

Kimberly Lamm (Duke University) analyses the “soundsuits” created by the African-American artist Nick Cave. These brightly flamboyant and elaborately adorned objects are costumes/sculptures that “extend the boundaries of the body’s recognisable form” by layering it with decorative objects and “girly throwaways” like sequins, buttons, rugs, vintage toys, flowers, stuffed animals, and ceramic figurines. Their joyful and colorful aesthetic references the African-American “will to adorn”, in particular the eccentric style of black dandies, producing what Lamm calls “queer elaborations” on the sartorial resistance of this historical figure. The soundsuits’s piled up and arranged layers increase the shape and height of the body, at the same time hiding all the markers of identity like skin color and facial features until the body inside the costume is completely reconfigured. Like the dandy’s outfits, the soundsuits incorporate masculine and feminine forms, revealing the “capacities of the black sartorial imagination to undo and re-imagine black masculinity’s contest with, and claim to, the regularised frames […] of white masculinity”. But beyond the aesthetic of “riotous joy” and “garishness”, the material configuration of the suits, that covers the eyes, nose and mouth suggests also “protection against intrusions both physical and perceptual”.

In fact, noting that Cave began working on them after the beating of Rodney King in 1992, Lamm argues that they are first and foremost a response to the racist. In fact, the suits provide the body with “a private space that cannot be easily seen into or through”, while rejecting transparency and identity categories, including, and most importantly, the category of aggressive hypermasculinity embodied by the the ‘Black Macho”, the hypermasculine nemesis of white suprematism which often operates by feminising and emasculating black men. The suit offers privacy and protection not only from physical violence, but from the implicit violence of having to conformism. Ultimately, Cave’s soundsuits speak of the long history of African-American sartorialism, insisting on dress’s power to “unhinge” normative expectations of self-display and gender and sexual identification, creating a material space for the free expression of black masculinity.

Christine Checinska (University of Johannesburg, VIAD)’s “Stylin’: The Great Masculine Enunciation and the (Re)fashioning of African Diasporic Identities” focuses on the style of “African diasporic peacock males” (a definition that poignantly reflects the flamboyant elements of local style) in the colonial Caribbean. Using Shane White and Graham White’s theory of African-American “stylin’”, Checinska draws a sartorial map of the emergence of the “new consciousness” among African slaves in plantation times. She also draws extensively from Kamau Brathwaite’s analysis of Caribbean language and Edward Glissant’s theory of creolisation to posit stylin’ as “a creolised non-verbal Nationan Language” influenced by West African models, writing of a “symbiosis between vernacular linguistic and sartorial expression [as] both are underpinned by the negotiation of identities”.

Checinska looks at the plantation system as the breeding ground of creolisation, which was as violent as it was “creative”. Stylin’ kept African histories, cultures, and traditions. In fact, self-fashioning was informed by many preoccupations and choices that recur in the dress styles of various African peoples. These included wearing voluminously draped cloth to communicate status, dressing the head (which had spiritual meaning), sporting garments in layered colours and patterns and showing a taste for striking hues often mixed in “syncopated colour co-ordination”. Further, the explosions typical of Caribbean verbal expression were “alive in the details of an outfit”, while the “orality” of Nation Language was paralleled by the performativity of stylin’ which, when the body moves demands a reaction from the audience (producing a non-verbal manifestation of “call and response”). Checinska stresses this emphasis on movement and “awareness of the body”, noting that “[s]tylin’ is as much about deportment, gesture, and stance as it is about individual items of clothing […] if the performance is ignored, meaning is lost”. Ultimately identities were “(re)fashioned […] in the midst of plantation slavery’s ‘ungendering’, feminisation and infantilisation”, with stylin’ emerging as “an act of transformation and freedom from […] constraints” that produced a “new consciousness of the self”.

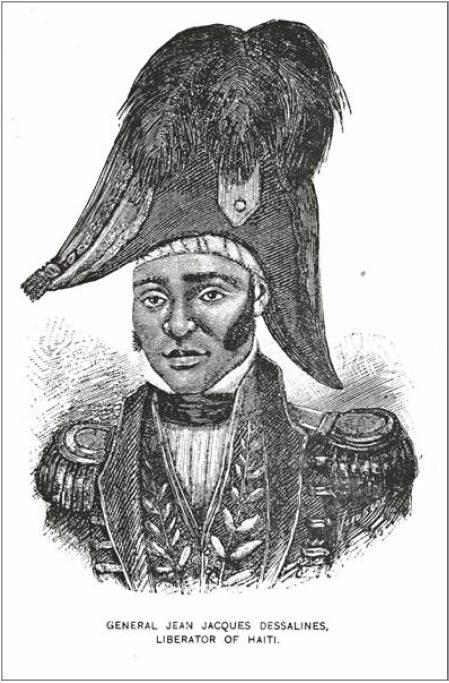

The second half of the article describes the Haitian Revolution as the event that ushered in a democratisation of dress, what she calls the “Great Masculine Enunciation” (as opposed to the understated man style of the Great Masculine Renunciation consequent to the French Revolution), that triggered the shift from undress to an adorned and elegant style. The leaders of the Revolution appropriated the embellished style of the ancient regime (Napoleon called them “gilded Africans” referring to their taste for extravagant surface decoration), adding a “West African inflection” that signaled the processual and “in-between” nature of their consciusness as free black man in the new world.

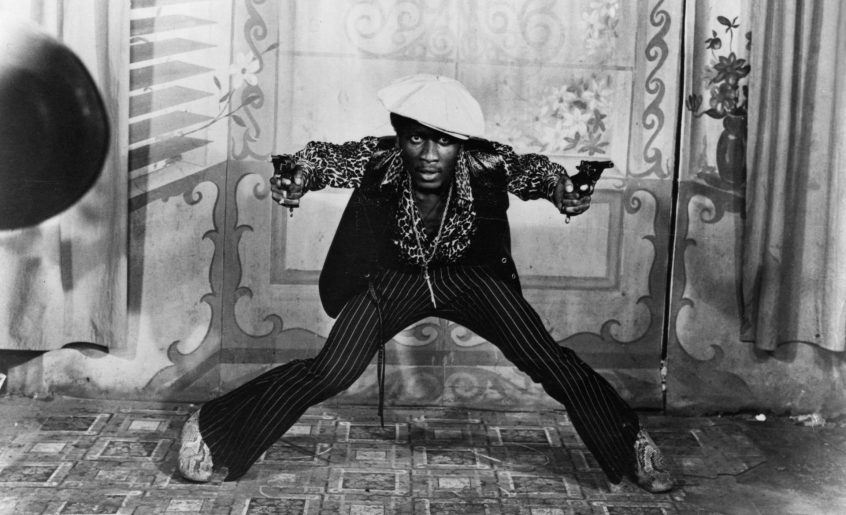

Michael McMillan brings us to England, writing about three instances of creolised black dandyism that dictated the rules of style for working-class men too: the style-fashion-dress of saga bwoys, rude bwoys and saggers from the 1950s to the present. Saga bwoys, who emerged in post-war times, took inspiration from the flamboyant style of African-American zoot suiters, notably wearing full pants to dance to jazz and calypso, a suit, and the “conked” hairstyle popularised by black and white rock’n’roll stars like Chuck Berry and Elvis Prisley. The saga bwoys influenced the style of the rude bwoys who embodied the cultural shifts of the ’60s and ’70s, popularising the look of Jamaican men and their “bad bwoy” attitude and fetish for weapons. Like saga bwoys, the rude bwoy brings his flashy style to the dancefloor, meticulously styling his hair and assembling garments and accessories that include “a Gabicci cardigan, silk skirt, Farah slacks, a Kangol hat, a Crombie coat […] as well as the mandatory folded handkerchief or flannel, and an Afro comb tucked in the back pocket of his trousers”.

Finally saggers are the most recent embodiment of what McMillan calls the “rhizoidal network of diasporic aesthetic exchange, transfer and appropriation” that produces creolised tropes of black masculinity. The saggers notoriously wear their pants low, revealing their underwear and pairing them with tight or string vests. They also wear “bling”, flashy accessories that display not only conspicuous consumption, but also opulence, enhancing the men’s visibility. The effect of such hypervisibility in mainstream culture and for the older generation of black men is the demonising and criminalisation of the youth, which is regarded as dangerous and offensive to values of self-respect and hygene.

These dress modes are all evoked to criminalise the men, associating them, in mainstream culture, with the iconography of a hypermasculine, dangerous black youth. For McMillan the styles are a creative expression of the “between and betwixt” nature of diasporic identity, its need to balance the very different values championed in the private and public realms these men navigate, and the ongoing negotiation between balance and rebellion. Citing Monica Miller’s study of the black dandy and R.F. Thompson’s concept of “cool”, he writes that “the creative agency of style-fashion-dress […] can be read as, on the one hand, an agreement to comform to what is considered respectable and, on the other, as resistance to that as a ‘symbol of transience and discomformities’”.

Cover Image: Jimmy Cliff as a rude bwoy in The Harder they Come (1973)