IBRAHIM KAMARA: FASHION OUTLAW

Having been out of the loop for 12 months means I get to do a lot of catching up – in fact, that’s all I’ve been doing these last months. While I was busy making friends with wee Ella a lot of new creatives have come into the spotlight, and I relish the overdose of visuals I get just by simply scanning Instagram. It’s too much and never enough – very stimulating.

Standing out in my feed is Ibrahim Kamara, 27, the Central Saint Martins graduate photographer-stylist who boasts collaborations with the likes of Nike, EDUN and Kenzo.

Born in Sierra Leone and raised in the Gambia, Kamara moved to the UK aged 16, where he was exposed to pop cultural influences that he claims were off limits to him while in Africa, due to a conservative upbringing. The clash between the early experience of war and European hyperconsumerist culture accounts for a futuristic aesthetic that mixes styles and references from both continents, while pushing boundaries and gender norms.

Kamara’s first major project, the series 2026, was on display at the group show Utopian Voices Here and Now at Somerset House in 2016. With photographs by South African photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman, 2026 establishes Kamara’s philosophy by envisioning what menswear will look like in ten years time.

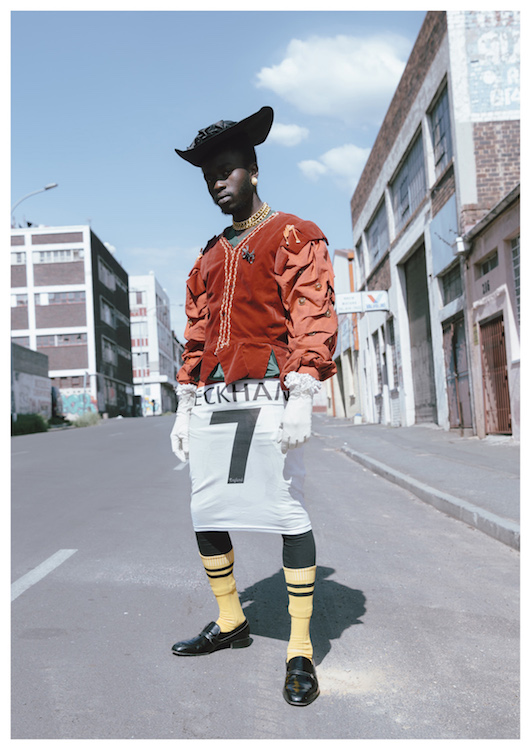

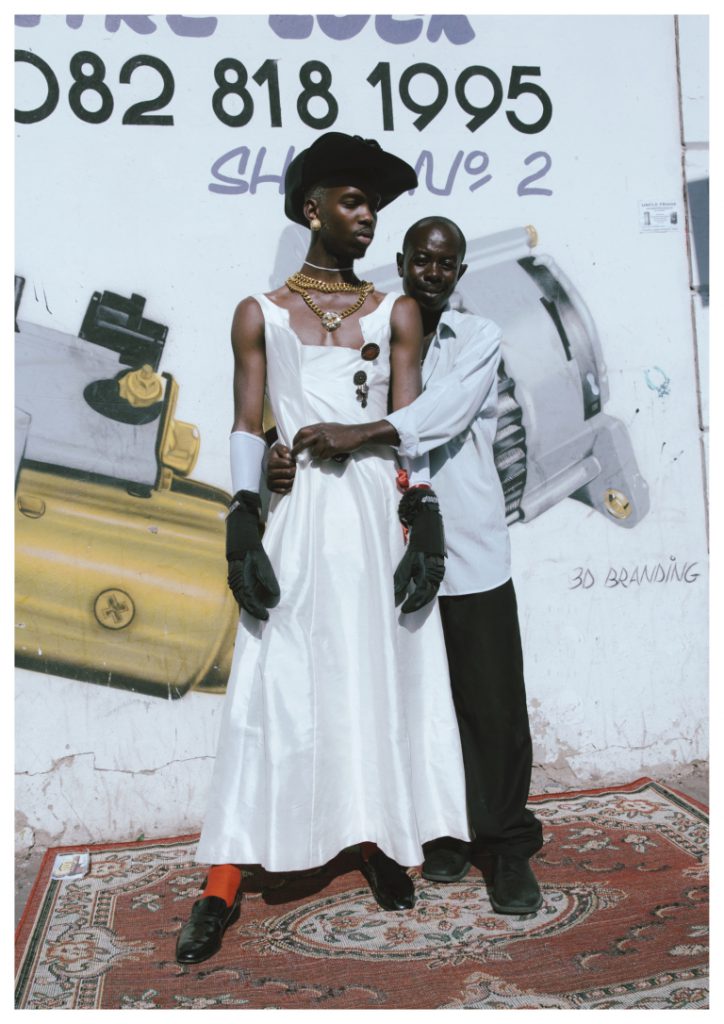

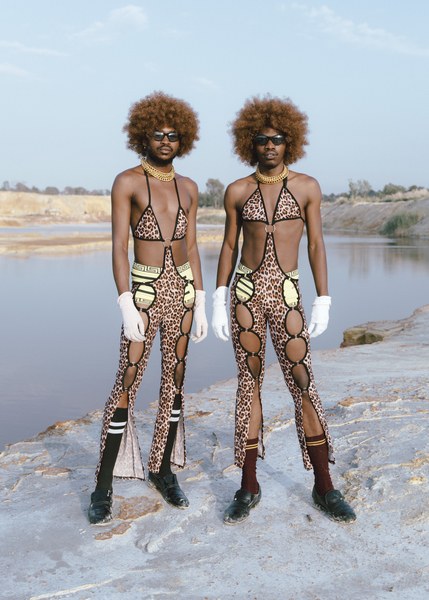

Johannesburg is the backdrop of a pastel-hued layout featuring models dressed in items sourced from local thrift shops, landfills, and fabric stores. The outfits channel a variety of styles while subscribing to no specific trend or look. The references include hip hop, YSL and John Galliano, but the way the clothes and accessories are worn and assembled create unique sets where football jerseys work as skirts, protective gear complements more formal attire and eccentric hats and bling are the go-to items of street-conscious styling.

The series intentionally frustrates the eye educated in Western fashion with an eccessive and flamboyant presentation that Kamara insisted should be context-specific. “In the developing world people see clothing differently to the way people see clothing here. They just put everything together [until] it becomes a style”.

Realised for a European audience, 2026‘s dreamy world shows empowered Africans that scorn comformism, performing their sense of self through a playful do-it-yourself aesthetic that breaks barriers, presenting an inclusive idea of fashion. The most representative shot of the series shows a boy in a wedding dress. Kamara often cites it to describe his idea of an “outlaw fashion world where anything goes”.

And indeed looking at the stylist’s many projects the message seems always to be: don’t take anything for granted, normalise the unexpected.

Clearly this approach encompasses ideas of gender and sexuality, which Kamara regards as inherently performative and fluid. His “Coachie” zine project, released for the “Stance” edition of Late at Tate Britain (2017) takes inspiration from the elaborate dress styles of the 16th century to image a non-normative concept of gender presentation.

As in 2026, the hypermasculine body is portrayed (again by Lee-Moolman) donning soft and delicately-coloured clothes that, along with Kamara’s playful poses, shatter the stereotype of the “tough” and “primitive” African man. In his stance is a powerful reclamation of innocence, a romantic idea of humanity and freedom of expression that Kamara relentlessly pursues as the political subtext of his endeavours.

FAKA, which have also been featured in 2026, are Kamara’s icons. The South African performance duo is a vocal supporter of black queer expression and the right to queer visibility in mainstream media.

These topics are at the heart of the “New Africa” aesthetic that Kamara and Moolman describe as a cultural movement that dismantles stereotypes about the continent while making space for the safe expression of alternative lifestyles and ways of being. New Africa lays the foundations for a world in which a man wearing make-up or a wedding dress as an everyday look is accepted, while establishing aesthetic rules that bring together glamorous and documentary photography, realism and imagination in ways that are representative of existing African urban subcultures.

The cover story for Candy magazine (2018), the styles for Burberry (2017) and Stella McCartney (2017) use dress and adornment as playful performance and fashion escapism to foreground the sensual pleasures of a parallel world where fashion indeed triggers the conversation but does not police it.

As I wait for that parallel world to gain substance and become the new norm, I think I will wait just a little longer in Kamara’s company before returning to the other playful reality of my and Ella’s world.