PAPA WEMBA, LE PAPE DE LA SAPE

I was saddened to hear of Papa Wemba’s death. An unexpected event that followed too soon that of another cultural icon and black dandy, Prince. Wemba collapsed on stage in Abidjan on Sunday 24 April , leaving a country – his native Democratic Republic of Congo – and a whole continent to mourn him.

Papa Wemba was the world ambassador of Congolese rhumba, but he was also a master fashionable: “le Pape de la Sape”, the father of sapologie.

Credited by many as the founder of the movement, he introduced it to the international crowd in the 1970s. Wemba’s public appearances, live performances, and music videos were défilés where he showed off elaborate outfits and design labels, acting as role model for generations of dandies in his native country and abroad.

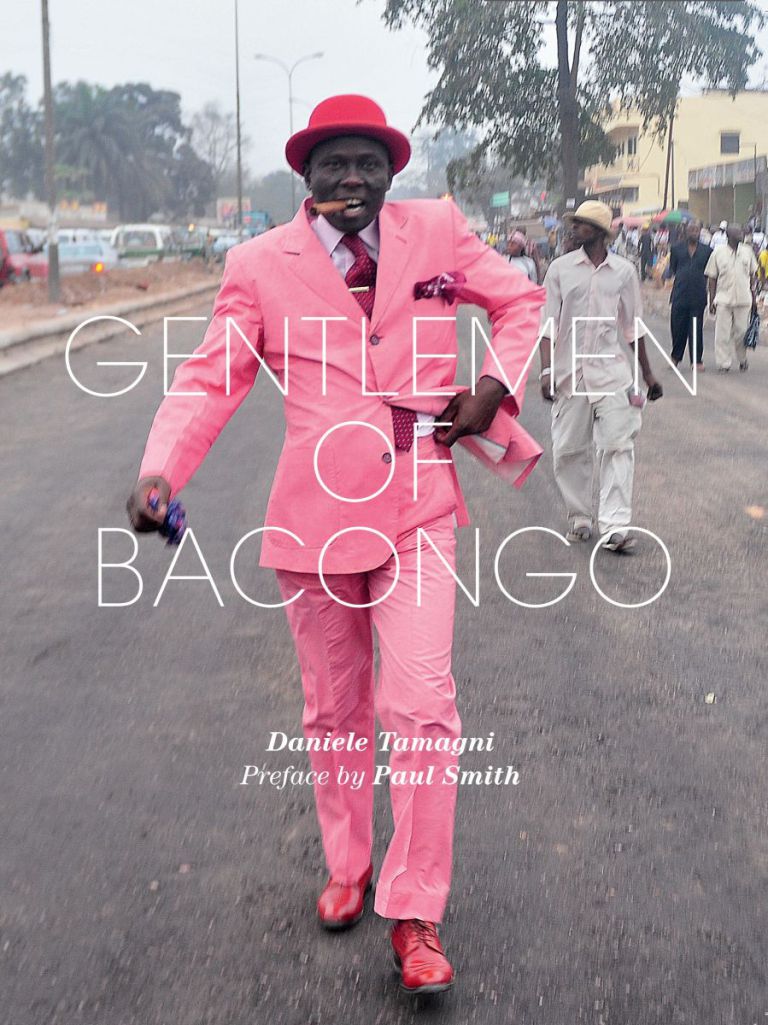

La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, or La Sape (from the verb se saper– to dress elegantly), began to form in the Congo region under colonial rule but it took off in the 1970s in DRC. To this day, it is regarded as the foremost expression of African elegance: a means of self-assertion that has been widely covered by Western commentators. In 2004 the film The Importance of Being Elegant (dir. G. Amponsah and C. Spender) was released, a chronicle of the history of La Sape set to a soundtrack by Papa Wemba; in 2014 Guinness realised a spot and mini-documentary about the subculture; sapeurs appeared in Solange Knwoles’ video “Loosing You”, and were the subject of various reports and a coffee table book by the Italian photographer Daniele Tamagni (2009).

Sapeurs are impeccably groomed, well-mannered, and, of course, dressed to the nines. Their insistence on personal hygiene and dignified behaviour is renowned, as is a passion for haute-couture garments, les griffes. “Sans la griffe, la sape n’existerait pas”, without griffes la sape does not exist, writes Didier Gondola (1999: 30).

And, indeed, sapologie revolves around the possession and parading of authentic designer clothes. In the song “Matebu”, Papa Wemba lists the labels he dreams of buying in Paris: Torrente, Mezo-Mezo, Valentino Uomo, labels he has actually worn and procured for the members of his band, Viva la Musica, and clan. In the documentary Papa Wemba: Le Roi de la Sape he shows his impressive possessions, saying that good clothes make a man feel “imperial” and “good inside”.

The religion of the cloth, la religion kitendi, populates countless accounts of sapologie and includes names such as Yamamoto, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Weston, Versace, and many others. A good reference to understanding this attachment to the fabric of elegance are Alain Mabanckou’s novels Blue White Red (1998 trans. in English 2013) and Black Bazaar (2009 trans. in English 2012). Here, the Congolese scholar chronicles the journeys of young Congolese men to Paris – “the city of elegance” (2013) – a journey that demands a literal shedding of their old clothes, their colonial skin, so to say. For the protagonist of Blue White Red migration begins at home as he and his friends of the Aristocrat clique carefully pick the clothes they will bring to Europe, refinement being their passport to modernity.

We didn’t buy just any clothing. There was linen, alpaca, crepe. Jeans were prohibited. An Aristocrat did not wear jeans. Those things were made for mechanics and plumbers, not for people like us with a fashion aesthetic. We also bought suits made of leather and buckskin. These threads, acquired with the help of our dues, were the property of the club, of all the Aristocrats. […] [W]e love ambience, the beautiful lifestyle, and we admire beautiful creatures such as those surrounding me here [in Paris]. Is it because the word sapeurs is going out of style little by little that we are now called Parisians? Clothing is our passport. Our religion. France is the country of fashion because it is the only place in the world where you can judge a book by its cover. That’s the truth, believe you me (2013, unpaginated).

In this passage, Mabanckou, himself a sapeur, shows that sapologie is a product of colonial and post-colonial relations as clothes provide a means to measure the worth of the black man. In fact, the appropriation of expensive items of clothing is an appropriation of the system of signification that is attached to them, particularly as signifiers of status and self-worth. Interpreting the dandyism of the sapeurs as a struggle for respectability, Didier Gondola (1999) comments on the importance that a clean and prim appearance has to dispel the ‘mal ville’, the biased perception of African masculinity, both at home and abroad. Elegance ‘uproots the body from the “mal ville,” rehabilitates it, and subjects it to a kind of therapy intended to erase the trauma caused by the myth of the “cursed race”’ (Gondola 1999: 31).

The ostentation of griffes is therefore a way to secure authority and social prestige in one’s own eyes and in those of one’s peers. It is certainly essential to understand gender politics and identity-making among African men – and to a lesser extent, women.

As both a material sign and an abstract referent of value, the griffe makes it possible to enact a form of positive self-portraiture by which anonymous individuals are reborn into persons of standing. So sapologie takes the colonial obsession with visibility and taxonomy to a new level: endowing the groomed body with the power to, literally, perform subjectivation.

As Michela Wrong notes in the article “A question of style” (1999), la Sape is a performance of self-assertion that takes place by means of elegance. She reports the words of Colonel Jagger, a sapeur she interviewed in Kinshasa, who proudly claims: “Do you remember John Travolta’s way of walking in Saturday Night Fever? Well, we were doing that long before he did” (22). Soon after independence, sapologie exploded in response to Mobutu’s politics of authenticity, which imposed that men wear the abacost jacket and abstain from wearing a tie, considered subversive. Strutting, peacocking, performing elaborate dance moves at parties, the sapeurs enacted a critique of the conformism imposed by the government, elevating the well-dressed man to the position of role model. “We don’t get mixed up in politics” (1999:24), adds Colonel Jagger in Wrong’s account, “This is a world where you can’t go out and shout in the street, where you suffocate, because there is no room to breathe. I have no weapons, so instead I create a world of my own” (1999:27-28).

Popular among disenfranchised and unemployed men, sapologie practices elegance as an intrinsically aspirational endeavour. It seeks differentiation to gain mutual recognition, crafting the aspirations and dreams of anonymous individuals into an alternative system of visibility that establishes communities of taste, where a shared passion for beauty encourages forms of mentoring and mutual assistance. The collective mourning for the death of Papa Wemba attests to this need of establishing and preserving a sense of community and dignity, beyond political and geographical affiliations. His loss is felt as the loss not only of a revered musician, but of a storyteller and custodian of collective values.

Bibliography and further references:

Bazenguissa, R. (1992). La Sape at la polique au Congo. Journal des Africanistes, 62( 1): 151–57.

Bazenguissa, R. and J. MacGaffey. (1995). Vivre et briller à Paris. Des jeunes Congolais et Zaïrois en marge de la légalité Économique. Politique africaine, 57: 124–33.

—— (2000). Congo-Paris: Transnational Traders on the Margins of the Law. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Gandoulou, J. D. (1989). Dandies à Bacongo. Le culte de l’Élégance dans la société congolaise contemporaine. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Gondola, D. (1999). Dream and drama: The search for elegance among Congolese Youth. African Studies Review, 42(1): 23–48.

Gondola, D. (2010). “La Sape Exposed!” High Fashion Among Lower-Class Congolese Youth: From Colonial Modernity to Global Cosmopolitanism’. In Contemporary African Fashion, eds. S. Gott and K. Loughran. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 157–72.

Mabanckou, A. (2012). Black Bazaar. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Mabanckou, A. (2013). Blue White Red. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tamagni, D. (2009). Gentlemen of Bacongo. London: Trolley.

Thomas, D. (2003). Fashion matters: “La Sape” and vestimentary codes in transnational contexts and urban diasporas. MLN, 118(4): 947–73.

Wrong, M. (1999). A question of style, Transition 80: 18-31.