THE NEVERENDING AFFAIR OF BLACKNESS AND THE SUIT

For 21st century Afrosartorialists, the suit is the material instantiation of exceptional cool. My newsfeed is filled with editorials and photostories that deploy the suit as the one garments that can fully magnify black empowerment and dynamism. It deconstructs symbolic abstractions that essentialize racial and ethnic identity, gluing Afro-diasporan blackness to positive visibility and diversity.

An article in the Lens section of the New York Times celebrates the British and Jamaican “rude boy” style, showcasing excerpts of Dean Chalkley and Harris Elliott’s photographic exhibition “Return of the Rude Boy”, showcased in London and Tokyo.

A few months ago Prisca Monnier’s wonderful and much needed work on female dandies appeared in Black Attitude Magazine, gaining huge visibility online and introducing the world to a thriving subculture of tweed-clad “queens” of style where hairdressing plays as important a role as stylin’ up.

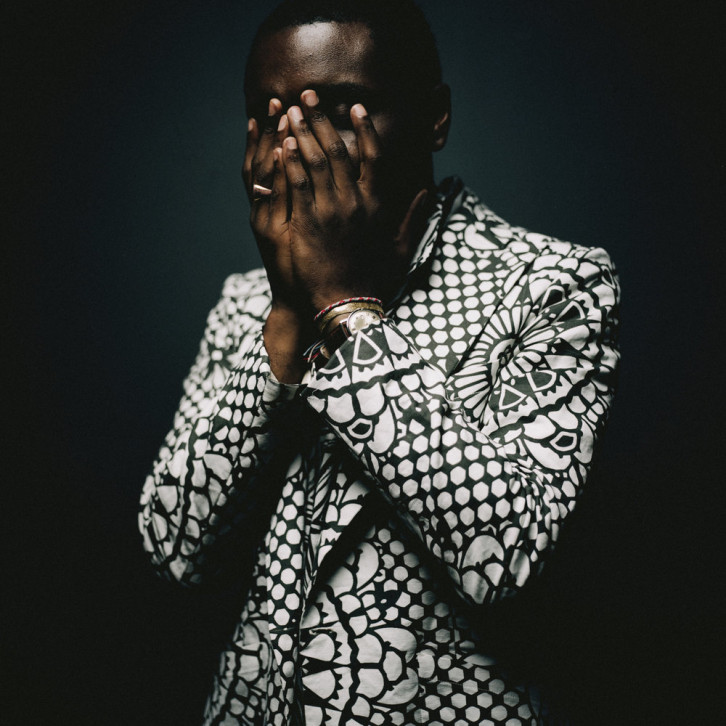

In early August, Marquelle Turner-Gilchrist introduced his photographic project of positive black masculinity on Blavity, with the goal “to use imagery to … paint new pictures of the black man and highlight the diversity and strength of black men”. The suit is the staple of this inverted stereotyping that also aims at showcasing the “diversity” of blackness.

Finally, the Afrosartorial fashion brand Ikiré Jones presented its Spring/Summer 2016 collection where suits are paired with Renaissance-era tapestry-styled silk scarves to create a displacing “afrofuturist” effect.

However, the suit is far from an unambiguous signifier and its relationship to blackness is filled with complexity, not least because Afrosartorials have had to claim the garment from white appropriation.

Following the end of WWII and the consolidation of consumer culture, the “gray flannel suit” channelled the dull conformism of WASP domesticity and the consumer dream of bourgeoise Americana that quickly extended to Western Europe. Novels like Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, films like Days of Wine and Roses and recent revisitations of that era, like Todd Haynes’s Far from Heaven and the TV show Mad Men, establish a visual correspondence between the suit and the corporate office, emphasizing the former’s function of containment, discipline, and coercive sociality within a hierarchical space delimited by the corporation and the suburban house.

When blacks the world over embraced the suit in those same decades (but also much earlier), it acquired a radical potential. It was a means to extend the normative project of Western citizenship to second-class men and women by vesting them with probity and dignity. As opposed to WASP Americans that felt robbed of their agency, the suit powered blacks up, but that too happened not without ambiguity.

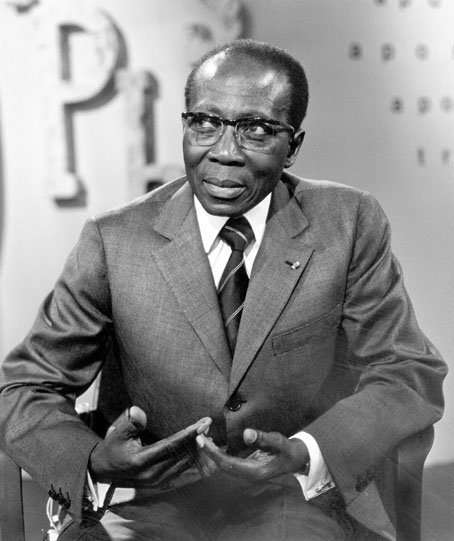

In Africa, many political leaders wore suits to remark their political maturity and commitment to independence from colonial powers. Most notably, Leopold Sédar Sénghor a key figure in the Senegalese fight for independence and also the country’s first president, always appeared in public wearing a suit. Noting that everyday dressing for most African societies articulates creative expression and ensures social-cultural preservation, Leslie Rabine rightly points to the “accumulated semiotic weight” of Senghor’s choice that “seem[ed] to violate in a sartorial register a basic principle of Négritude: the vehement rejection of French colonial policies of assimilation” (2013: Kindle edition, unpaginated). Indeed, within the colonial hierarchy the unadorned suit was essential to the exercise of foreign and intra-colonial power. In effect, domination took root also via a sartorial translation: the garment that symbolized the enlarged, anonymous middle-classes of Europe, in Africa became a red harrow of the colonizers’s exceptional, god-like status.

Senghor’s sartorialism is therefore essential to understand its vision of Africa and of Africans vis-a-vis the world. Interestingly, Rabine, whose review of this topic was prompted by photographic material, turns to the politician’s poetic production where images of dress and body abound to explain not his actual philosophy, but its present value. In Rabine’s analysis the suits are never a material object, but images of objects that have references in reality and fiction. “The photos approach the Senghorian living forms […] by representing to future viewers […] a conjunction between image, reality, desire, and ‘imaging consciousness’ that was necessarily absent from the lived experience in the present tense” (ibid.)

I think the key to understand the neverending affair of blackness and the suit can be explained by looking at this overlapping of reality and desire. The garment seems to retain a porosity that makes it the ideal vehicle to perform black embodied emancipation across digital platforms and cultures across the world.

References:

Rabine, L., “Photography, Poetry, and the Dressed Bodies of Léopold Sédar Senghor” in African Dress: Fashion, Agency, Performance, (London, New Delhi, New York and Sidney: Bloomsbury, 2013) 171-85.