READING FILES: NICOLE R. FLEETWOOD, TROUBLING VISION (2011)

Troubling Vision (2011) is a key text for studying blackness and black identity from the point of view of visual studies. I am compelled by Fleetwood’s analysis of the double bind of blackness as something that saturates the field of vision, “troubling it” while also remaining complicit to, and thus reproducing, normative framings of racial difference. At the core of her analysis is the critique of America’s insistent cultural and visual “investment in black iconicity” (11), which denies visibility to blacks as “ethical and enfleshed subjects” (16). The spectacularization of blackness entails that the image becomes iconic, “function[ing] as an abstraction, as decontextualized evidence of a historical narrative that is constrained by normative public discourse” (11). Troubling Vision critically addresses the presence of the black body as “commodity fetish” in American visual culture, mapping alternative paths of black visuality (112).

The politics of iconization and the value of blackness as a source of capital are addressed in the chapter entitled “‘I am King’: Hip-Hop Culture, Fashion Advertising, and the Black Male Body.” Here, Fleetwood analyzes the rise of the hip-hop fashion industry in the 1990s, propelled by the activities of moguls the likes of Russell Simmons, Sean Combs, and Jay-Z, as a manifestation of “the marketing of youthful and racialized alterity as a stylized and reproducible commodity” (176). The concern with the commodification and reproducibility of blackness makes her exploration of this specific instance of black American culture a core reference of my examination of African vernacular dress as a marketable signifier of “cool” and attitude.

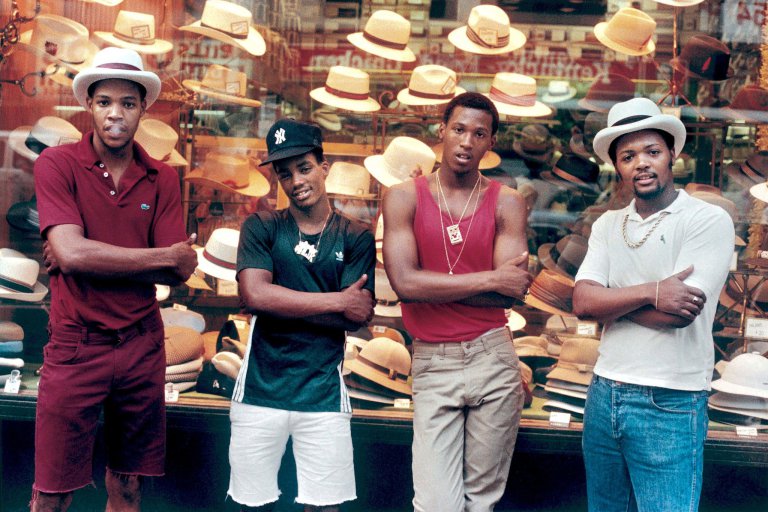

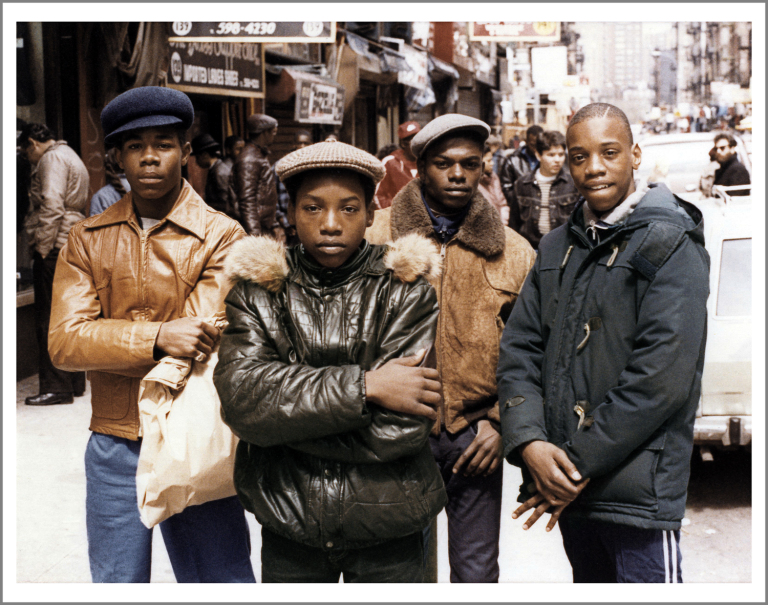

Fleetwood looks at hip-hop fashion, particularly at the advertising strategies of Simmons’s Phat Farm brand and the public presentation and look of Combs, as the sites of a “visual resignification” of the symbols, meanings, and social conditions of postindustrial, urban black life. The chapter begins by referencing the photography of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jamel Shabazz that exemplify the post-civil rights iconicization of the black male body rooted in modern-day flaneurism. These works show that since the 1970s the city, New York especially, has defined racialized embodiment and self-presentation, functioning as material limit and horizon of black self-definition. The engulfing and oppressive urban milieu invites self-reflection and a wish to assert one’s worth through visual and material means, something that is also expressed by hip-hop culture. Fleetwood notes that Shabazz worked with black newyorkers “to produce idealized images of urban black style and life” (150). Further, she reports that Hendricks photographed “blacks whose claims to pictorial posterity resided neither in deeds nor dictates but in their clothes, carriage, and color” (149). In both instances, dress and posture channel a desire to articulate black self-perception in glamorous ways that associate authenticity with a display of material possessions and ownership of white signifiers of affluence (gold chains, leather jackets).

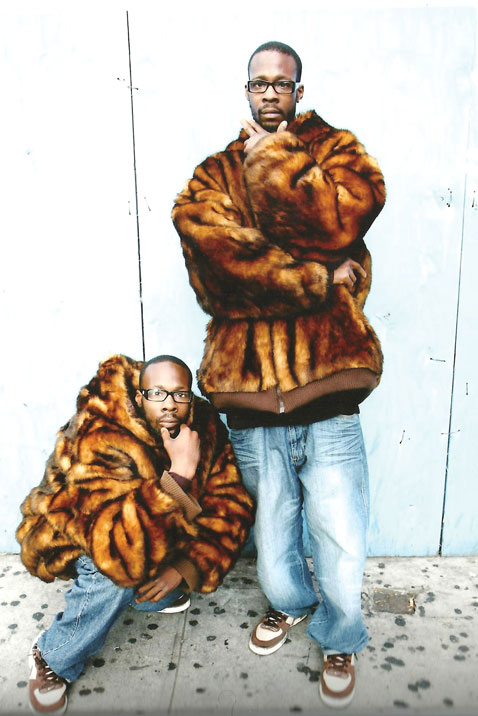

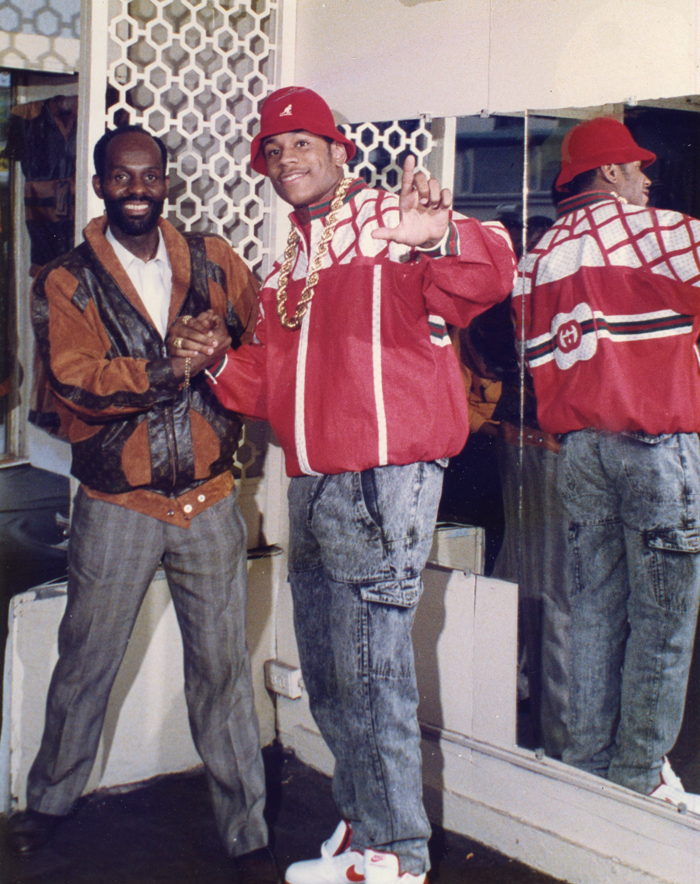

The hip-hop fashion system likewise showcases urban black masculinity and its investment in “ambivalence” and “change” by redefining glamour through consumption of “upper-class status symbols” and luxury items “that have been coded as whiteness and privilege” (154). Citing Fred Davis, who writes that ambivalence and change drive the endless regeneration of the fashion industry, Fleetwood notes that the success of hip-hop fashion is due to a “merging” of “normative icons of Americana” with “nonnormative or underrepresented (in the realm of fashion) bodies” (166). Laura Kuo’s study of the “commoditization of hybridity” is also referenced as a source to understand hip-hop’s commercial value as “consumable difference” (173).

A play of disembodied and embodied signs, of icons of privilege and bodies from the ghetto, sustained the consolidation of hip-hop fashion in the early 1990s as a universal (rather than gender- and race-specific) signifier of identity. According to Fleetwood, at the root of hip-hop’s transformation from niche market to global culture industry is its endorsement of American patriotism in discourse (she references Barthes on written clothing in her analysis of the rhetoric of hip-hop fashion) and design motifs and the deployment of brand logos as reproducible abstractions that signify wealth and capitalist citizenship. “Apart from denim and seasonal colors, the more popular hip-hop fashion styles are based on reproducing the three colors of the American flag in patterns and fabrics that both reference and redefine the nation and patriotism. What distinguishes the articles of clothing is the company’s label placed strategically on the products” (161).

Today, hip-hop is one of America’s most successful culture industries. Its absorption of “the restrictive visual codes” of mainstream fashion and endorsement of “the normative ideology of American capitalism and nostalgia” guarantee its infinite reproducibility (160). Mobilizing the mythology of urban living, it envisions and substantiates the appeal of wealth and financial accumulation. But its strong Americanist message is just as powerfully delivered by the meanings associated with the black and Latino bodies on display in advertisements and billboards. These bodies deliver a positive message of American multiculturalism and, by association, of inclusion and self-affirmation, especially as they are relocated, as in an advertisement of Phat Farm analyzed in the chapter, in the pacified context of a suburb, the quintessential symbol of social acquiescence and conformism. Fleetwood, however, underlines the unresolved tensions encapsulated in this juxtaposition of signifiers of Americana when she observes that the “symbols of patriotism incorporated into hip-hop fashion and consumer goods work together with notions of urban black masculine alterity to create a character who is at once an ultra-stylish thug and the ultimate American citizen” (155). (Sidenote: read this opinion on Jay-Z as a style icon).

Articulating both inclusion and exclusion, entitlement to capitalist accumulation and exceptionalism, the iconic body of the black urban dweller clad in hoodie, baggy jeans, and boots is undergoing a further transformation. In the final pages of the chapter, Fleetwood writes about the emergence of a “new urbane self-fashioning” promoted by a younger generation of artists, most notably Pharrell Williams. “No longer does the black male icon of hip-hop signal threat. Instead audiences interpret the posturing as a performance of racial alterity, of self-conscious differentiation based on familiar tropes of race” (174). The full incorporation of this fashion aesthetic into the mainstream is signaled by the fact that the traditional insignia of hip-hop dress are mixed (or “sampled”) with elements drawn from Japanese anime and skateboarding, defining a “hybrid” style of urban masculinity. This further move towards hybridity intensifies the marketability and global appeal of blackness, abstracting it from the social, historical and cultural conditions that produce ambivalence and change as a survival strategy.

Reference:

Fleetwood, N. R. (2011), Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.