ANTHONY BILA: BLACK HISTORY MARCH. WHEN FASHION PLEASES TO TEACH EMPOWERMENT

Last week South African photographer and video-maker Anthony Bila released a new volume of his yearly series “Black History March.” The 3-minute video features the fashion duo Sartists and pays homage to 1950s fashion with beautiful visuals and the dandies’s classic styling.

Following a project that they have been pursuing for some time and independently of each other, Bila and the Sartists join forces to plant a time capsule in the online clutter and promote racial consciousness, purposefully posting the outcome of their collaboration a week after the end of February, the designated month of Black History. The intention behind this, explains Bila in the text that introduces the video, is “to dispel the notion that black history needs a ‘special month’, the shortest month of all no less”, breaking with its limitations and bringing the ode to blackness to other, non-sanctioned times and commemorating practices. He continues: “My thoughts about black history are that it should be venerated just as any other significant part of history is, at every given opportunity. The name of the series is a double entendre. March being the month we are in and march in the sense that we soldier on, as a people moving forward but never forgetting to reflect and look back at where we have come from. Something I believe we should all do.” Bila’s political agenda complement the Sartists’s commitment to use fashion as a visual statement and marker of black empowerment.

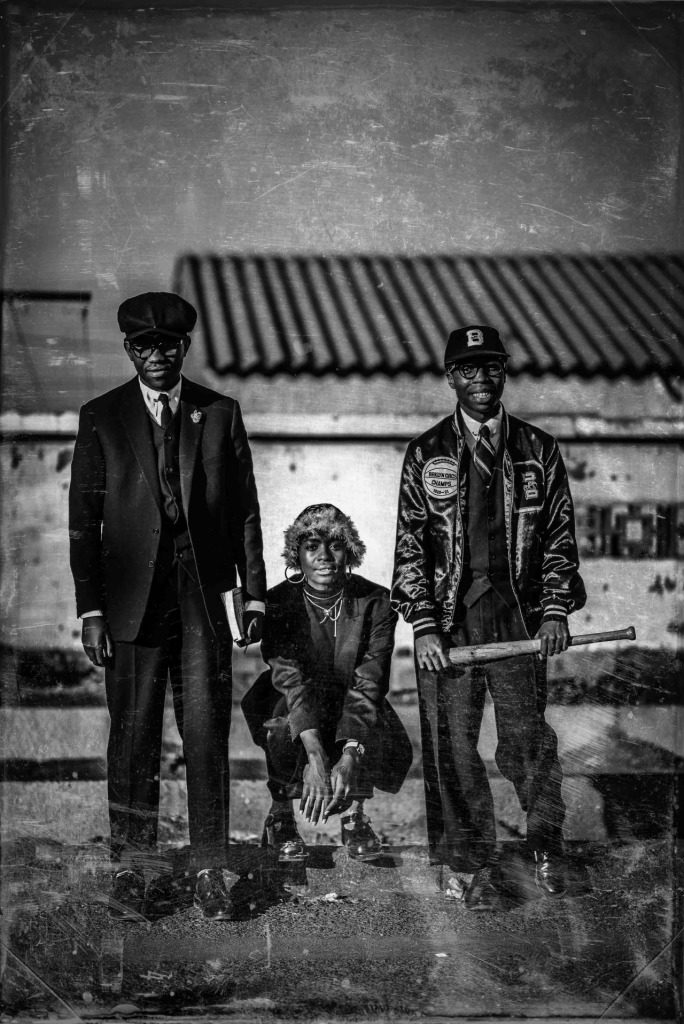

The short production creates an evocative, sepia-toned atmosphere of vintage township life, where the two fashionable protagonists move. The Sartists are caught at home, sitting on the sofa in their underwear. L. Armostrong plays as the camera records their dressing routine, going in and out of focus as it rests on the details of the outfits – like an old machine would do. The youths put on pressed shirts (one black and one white), ties and tie-clips, slacks (the black shirt goes with what look like tweed trousers with a frayed bottom), leather belts. One of the two dandies puts a waistcoat on his white shirt. The suits come in gray tweed (?) and pinstriped black, the shoes are a shiny leather, and boots with a periwinkle trim. Finally, after having put on black rimmed glasses and fedoras, the protagonists move from the dining room to the kitchen, where they smoke and sip drinks from enamel cups.

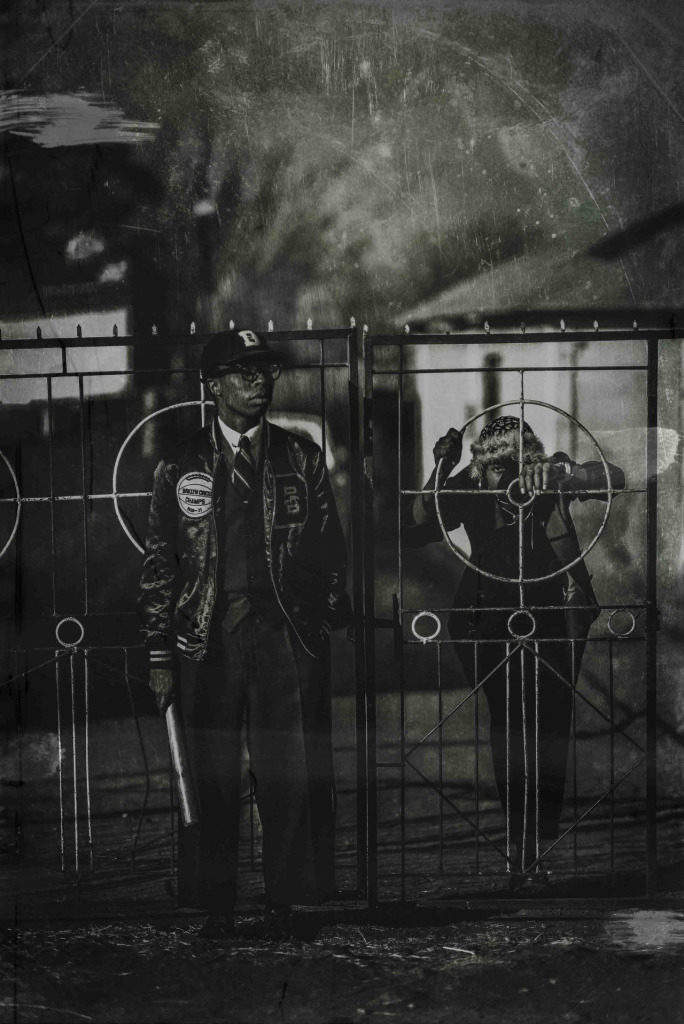

The air is of carefree, but poised enjoyment. The guys are in no rush to end their leisure. The gray-dressed protagonist sits on the threshold of the door, letting the outside light in the dim room. When the Sartists leave their modest house it is afternoon and the camera follows them as they make their way through the township’s alleys, where clothes stereotypically, but also realistically, hang drying in the sun, street are unpaved, and houses have roofs of corrugate iron. A fence encloses the place and bars the view. The camera continues going in and out of focus, contributing to the dreamy atmosphere of the spectacle. The Sartists rest by the fence, smoking. Their shadows on the road are a literal metaphor of their aesthetic function of beautiful conjurers of fantasies, existing as both real and imagined entities. After framing their faces in two individual close-ups the camera finally shuts down, but the music lingers on.

I wrote about the Sartists’s brand of conscious fashion and how these stylists reclaim the suit, often restyling second-hand items bought at local markets, as a uniform of black empowerment, dignity, and pride in an old blog post. In my forthcoming article on African retrospective sartorialists I look at their love for retro clothes through H. Jenß’s notion of “textile flashback”. Creating iconic portraits of masculine sophistication with vintage apparel, helps them to “uses the potential of dress as a cultural signal of time and an important component of cultural memory, historic consciousness and imagery. In fashion […] retro gains a very particular quality, because with the garment as the object closest to the body, time and history […] are literally in touch’” (Jenß 2005: 179). This regenerative attitude of bringing discarded garments back to life is a core aspect of present-day dandyism that differentiates it from its Euro-American homologues, where new and branded clothes are usually favoured. Most importantly, it is the immediate referent of the sartorial aesthetic through which the members of the subculture proactively consume history and express racial consciousness.

In his visual work, Bila too looks at the past as a repository of timeless teachings on the worth of racial affirmation. But while the Sartists actually excavate the past, styling themselves in original garments and accessories from past eras, Bila crafts digital re-imaginations of history, manipulating the images to make them look like vintage material. His flashbacks play not on the evocative allure of a material archeology that unearths forgotten times and anonymous histories, but on the need to practice an aesthetic archeology of the vernacular in the first place.

This approach invites a conscious engagement with memory, since the beautiful shots force us to reflect on our fascination with the past as an aesthetic territory, but one where, nonetheless, the encounter with beauty prompts self-reflection. The experience of visual pleasure that we derive from Bila’s work inspires a perceptual short-circuit where the spectacle is both familiar and unknown. Are the images we are enjoying a realistic recreation of historical situations, or are we misinterpreting this feeling of recognition? Could it be that the implicit knowledge that we exercise while looking is the outcome of an idealisation of the past? After all, what do we know of African and Afro-diasporic vernacular culture of the emancipation decades (and I am here referring explicitly to people like myself who have no first-hand experience of it)?

Bila’s work, like that of other emerging African artists who take inspiration from family archives and histories, promotes a rearticulation of the relationship between race and culture based in the affective allure of a system of recognizable signs. Using a documentaristic style to generate a visual narrative of black legitimacy, beauty, and affirmation, Bila make history from scratch, texture, scraps of fiber (the garments worn by his protagonists), natural elements (including light – a prominent element of his videos), and acoustic traces that play on memory to generate a positive sense of community.

As in bell hook’s description of black aesthetics, “Black History March” “seeks to explore and celebrate the connection between our capacity to engage in critical resistance and our ability to experience pleasure and beauty” (1990: 111). It trains the eye to engage beauty not as a universal ideal, but “as a force to be made and imagined” (1999: 104) that “work[s] with space to make it livable” (1999: 112).

References:

hook, b. (1999), ‘An aesthetics of blackness: strange and oppositional’, in b. hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics, Boston: South End Press, pp.

Jenß, H. (2005),‘Sixties Dress Only! The Consumption of the Past in a Retro Scene’, in A. Palmer and H. Clark (eds.), Old Clothes, New Looks, Oxford and New York: Berg, pp. 177-195.