THE REDUCTIVE AESTHETICS OF ‘AFROPOLITAN’ FASHION

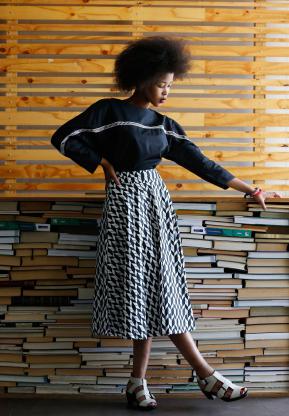

These past few days I have come across two (more) articles documenting the success of African fashion with Western customers, one by a niche publication, and another one by a major news platform. In both cases, ‘African dress’, a rich signifier encompassing a host of different practices and trends, is reduced to a very specific and limited typology of sartorial fashion, aimed predominantly at a female audience of middle-class, ‘chic’ urbanites. Pencil skirts, blazers, light shirts, sleeveless tops are combined into vibrant ensembles where eccentric accessorizing, hues, patterns, and fabric mix and overlay, creating almost painterly, certainly edgy and eye-catching effects. The articles’ approach to the subject is representative of the larger trend of African and non-African actors of mobilising such a narrow sartorial imaginary and set of signifiers of ‘authentic’ Africanness to promote a narrative of continental advancement driven by lifestyle and taste trends.

The first article is a post appeared in the blog Nothing but the Wax that advertises the latest entrepreneurial accomplishment of the Cameroonian designer Julienne Biyah, owner and CEO of the fashion brand OWL, launched in 2013. The post informs us that Biyah opened an ‘Afropolitan concept store’ in Paris that sells clothes, accessories, food, as well as showcasing design from selected African artists. The aim is, in fact, to increase the visibility and marketing potential of ‘Afro-chic’ using this space to host the creations of talents from the continent on a monthly basis.

In line with this goal, the boutique’s ‘Afropolitan’ style mixes different elements, little of which reference actual African dress practices. The pictures that I found online show a visual and sensorial impression of cosmopolitan glamour, where items in colourful prints are displayed on polished, wooden surfaces and bare, metallic racks. A combination of minimalism and ‘ethnic’ decor contributes to the cosmopolitan feel of the boutique.

Portraits of African subjects in black and white, some of which show women in what seems to be traditional attire (fur is involved), share wall space with glass shelves and a sign fabricated with different textures and leaves indicating the “Comptoir tropical” area, where Cameroonian jams and other delicacies from the continent are sold. Rest space is provided by an armchair adorned with a pillow in a textured pattern similar to the wax fabric of the clothes on sale.

OWL’s philosophy is to facilitate the meeting of Africa and fashion, and a look at the store and the brand’s catalogue readily shows that this encounter creates a style where urban chic is produced by spicing up the ensembles with pieces realized in wax print, adding inserts of ‘traditional’ fabric, or employing prints and designs that somehow reference ‘Africanness’.

Indeed, such textiles, which are an item of mass-consumption in Western and Central Africa, are representative of OWL’s brand image. The ‘About’ section of its e-store states that they are the building block of its ‘chic, urban and original’ aesthetic. In a previous post I have written about the story and importance of wax textiles for African sartorial practices, particularly their uses for colonial and post-colonial exchanges. The present currency they are enjoying among non Africans only attests to their continuing power as channels of syncretism, but also of cultural appropriation. Ultimately, if Afropolitanism is an ‘awareness of the interweaving of the here and there’ (Mbembe 2007: 28), then wax textiles are a significant index of the contamination of cultures that has always marked the Afro-diasporic experience, but also of an attendant form of ‘hipsterism’ (Dabiri 2014) that seems to define contemporary racial awareness.

‘Africanness is also, and increasingly so, mobilized in the arena of lifestyle’, observes Marleen de Witte (2014: 263). ‘Thriving on aesthetic appeal, design, and marketing [cultural entrepreneurs] vest “being African” with an aura of urban cool that attracts increasing numbers of young people and provides them with the materials […] with which to flesh out their – often newly found – identities’ (Ibid.)

A similar approach to elements of fashion, such as vibrant and patterned fabric, as a visual signifier of cosmopolitan ‘Africanness’ appears in the second article I encountered: a report by NBC News on the ‘break into the mainstream fashion’ Africa’s home-grown designers. The piece places the rise of an international demand for fashion items produced in Africa in the context of two phenomena: changing economic conditions in some parts of the continent, particularly the Sub-Saharan region where there is now a growing middle-class, and evolving consumer awareness and demand for better-quality and ‘authentic’ products. Once again, the article suggests that what Africa has to offer in sartorial terms is a promise of advancement and dynamism.

Reference to the host of stores by African designers that are opening up in London, Singapore, and New York, and to the worldwide demand of clothing items created and manufactured locally (as in the case of the Ethiopian shoe company soleRebels, or the South-African retailer Kisua) shows that African fashion travels and makes one travel — follows a list of celebrities wearing Afro-sartorial products, including Michelle Obama and Beyonce. Through the stories of ‘Nigerian lawyer-turned-designer Duro Olowu’ and ‘Ghanaian entrepreneur Samuel Mensah’, the article replays the Africa rising narrative of ‘a continent which is earning a brighter reputation beyond stories of war and disease.’ An article published over a year ago states that ‘Bolstered by recent advances in economic growth rates, Africa has been turned into a brand, a product to be packaged and sold on the merits of its financial worth”, and certainly the narrative about Afropolitan fashion provides a captivating framework to endorse this reading.

Bibliography:

Emma Dabiri, “Why I’m not an Afropolitan”, Africa as Country, 21 January 2014, http://africasacountry.com/why-im-not-an-afropolitan/

Achille Mbembe, “Afropolitanism” in Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent(Johannesburg: Jacana, 2007).

Marleen de Witte, “Heritage, Blackness and Afro-Cool”, African Diaspora, 7 (2014): 260-289.